Began to covet the role of “God” after the Human Genome Project

- Mifepristone: A Safe and Effective Abortion Option Amidst Controversy

- Asbestos Detected in Buildings Damaged in Ukraine: Analyzed by Japanese Company

- New Ocrevus Subcutaneous Injection Therapy Shows Promising Results in Multiple Sclerosis Treatmen

- Dutch Man Infected with COVID-19 for 613 Days Dies: Accumulating Over 50 Virus Mutations

- Engineered Soybeans with Pig Protein: A Promising Alternative or Pandora’s Dish?

- Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS): A Tick-Borne Threat with High Mortality

Began to covet the role of “God” after the Human Genome Project

- Red Yeast Rice Scare Grips Japan: Over 114 Hospitalized and 5 Deaths

- Long COVID Brain Fog: Blood-Brain Barrier Damage and Persistent Inflammation

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- What is the difference between Atorvastatin and Rosuvastatin?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Began to covet the role of “God” after the Human Genome Project. Twenty years after the Human Genome Project, we began to covet the role of “God”.

Twenty years ago, our knowledge of genes was so limited that when the draft of the human genome was released, it attracted global attention.

From TV to newspapers, the media was reporting the incident one after another. Today, 20 years later, we are no longer satisfied with discovering new genes, but editing or rewriting genes, understanding human life, old age, sickness and death, improving crop varieties, and even creating genes that have never appeared before. To some extent, we are playing the role of creator.

This article will take you back to the exciting Human Genome Project, how it went from an ambitious beginning to a hesitant and difficult middle, and finally achieved a happy result for everyone. What can we do with genes in the next 20 years, and what surprises will we find?

In February 2021, the journals “Science” (February 5) and “Nature” (February 11) published a special issue of the Human Genome Project to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the publication of the draft of the human genome.

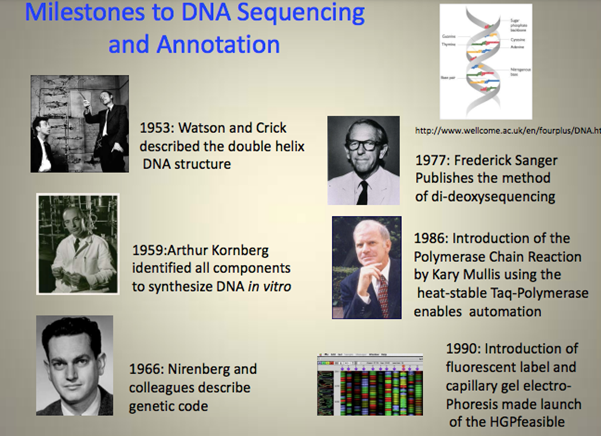

In 1953, Crick and Watson discovered the double helix structure of DNA; in 1977, Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger invented the method of DNA sequencing.

Milestones in genomics research, picture from lehigh.edu

Milestones in genomics research, picture from lehigh.edu

Subsequently, the DNA sequences of some simple organisms including the EBV virus were sequenced successfully. Although some scientists recommend sequencing the human genome, facing the huge scale of the human genome of 3 billion base pairs, continuous research funding has become a problem for researchers.

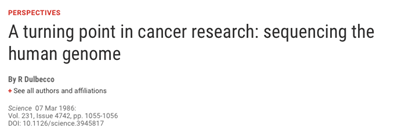

In March 1986, the US Department of Energy (DOE) held a meeting in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to discuss the human genome sequencing project. Renato Dulbecco, winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, published an article in the journal Science, and pointed out that the sequencing of the human genome will be a key turning point in cancer research.

In June of the same year, Leroy E. Hood (Leroy E. Hood, Lasker Medalist in 1987) and Lloyd Smith improved the cumbersome Sanger sequencing method and invented The world’s first automatic DNA sequencer was established.

It can be said that whether it is from actual needs or technical support, the time to sequence the human genome is relatively mature.

In April 1990, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Energy jointly issued a five-year human genome plan, which includes the sequencing and mapping of human and model organism genomes, data collection and analysis support (algorithm improvement, software design and development) Etc.), technology research and development and transfer, etc.

In August of the same year, NIH began large-scale genome sequencing of four model organisms, including Mycoplasma capricolum, Escherichia coli, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Two months later, NIH and the Department of Energy “righted the clock” and officially announced October 1 as the official start time of the “Human Genome Project.”

Since then, the “Human Genome Project”, known as the “Moon Landing Project” of life sciences, has been formally embarked on its journey, which has been involved in the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Japan, and some countries’s scientists. This journey has taken nearly 13 years.

Of course, there were also some “episodes” during this period. For example, the biologist and “scientific maniac” John Craig Venter (John Craig Venter) had a disagreement with the “Human Genome Project” team on the genome sequencing data sharing policy.

Angrily left NIH, and established Celera (Celera) biotechnology company in May 1998, claiming to complete the human genome sequencing work within 3 years.

So NIH had to improve efficiency and speed up the progress so as not to be preempted by Venter. In fact, this “competition” has also promoted the “Human Genome Project” to proceed more quickly.

The final result is still very happy (note: in many people’s eyes, Celera won the competition), the International Human Genome Sequencing Alliance and Celera Biotechnology Company on February 15, 2001 and February 2001, respectively The draft of the human genome was published in the journals “Nature” and “Science” on the 16th.

Clinton announced the completion of the human gene draft, the picture is from heterodoxology.com

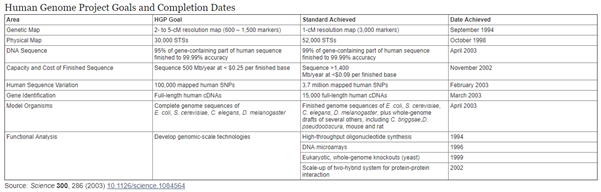

The “Human Genome Project” was finally completed in April 2003, announcing the arrival of the “post-genome era”. So, what impact does the “Human Genome Project” have on current scientific research?

Alexander J. Gates of the Network Science Institute of Northwestern University and others pointed out in an article in the journal Nature on February 11 that the “Human Genome Project” has greatly improved our understanding of genes and their regulatory elements, and Assist researchers to determine the targets of many drugs [1].

The most notable feature of the “Human Genome Project” is the huge amount of data. During the 13 years of the project’s implementation, the number of “annotated” genes has increased rapidly.

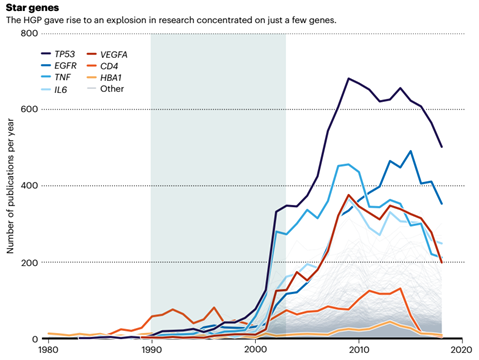

Since 2001, the number of academic papers on protein-coding genes has ranged from 10,000 to 20,000 per year, as long as they focus on star genes such as CD4, TP53, TNF, and EGFR.

This is all thanks to the “Human Genome Project” changing the data acquisition method from “single hook fishing” to “fine net fishing”.

In the past 30 years, the publication trend of several human “star genes” papers, as can be seen from the figure, the number of papers published has increased sharply after the success of the HPG project

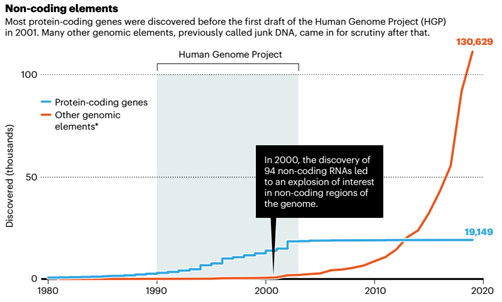

The “Human Genome Project” has further determined the biological importance of non-coding sequences in the genome. Changes in these sequences will not affect the sequence of the protein, but will interfere with the protein expression network, which in turn affects biological functions.

After 2000, scientists’ interest in understanding non-coding regions of genes has not diminished.

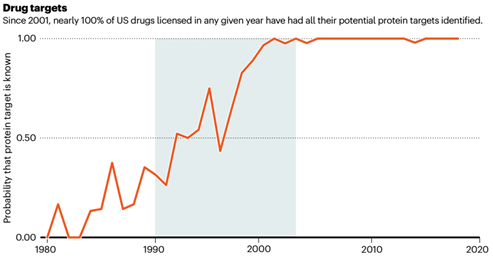

Before 2001, the probability of identifying all protein targets of a certain drug was less than 50%. After the completion of the “Human Genome Project”, almost every drug passed in the United States has a clear target description.

The “Human Genome Project” not only promotes the development of biology and biomedicine, but also actively deepens the integration of the “big science” of multidisciplinary cooperation.

Since the beginning of this century, information science and computer science have developed more rapidly. The “Human Genome Project” is a successful case of in-depth cooperation between genetics, biochemistry, molecular biology and information science. Since then, various “omics” have appeared and jointly constructed The “big data” era of life sciences.

At the same time, with the continuous update and iteration of computer algorithms and the gradual reduction of sequencing costs, personal genomics is entering people’s daily lives. The popularization of genome sequencing will help us understand the genetic diversity of human beings, and ultimately serve the development of medicine and protect human health.

Twenty years later, when we review the Human Genome Project, humans are no longer satisfied with discovering genes, but modifying genes, editing genes, or even creating a gene that has never appeared before.

What else can we do with these basic human genetic units in the next 20 years? At least we have already felt the current gene therapy is developing day by day, and we are reaping the fruits of the “Human Genome Project” that year.

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org