H1N1 flu virus may be “direct descendant” of the 1918 influenza strain

- EPA Announces First-Ever Regulation for “Forever Chemicals” in Drinking Water

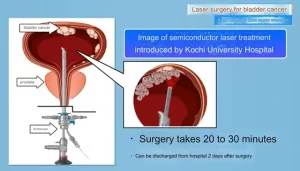

- Kochi University pioneers outpatient bladder cancer treatment using semiconductor lasers

- ASPEN 2024: Nutritional Therapy Strategies for Cancer and Critically Ill Patients

- Which lung cancer patients can benefit from neoadjuvant immunotherapy?

- Heme Iron Absorption: Why Meat Matters for Women’s Iron Needs

- “Miracle Weight-loss Drug” Semaglutide Is Not Always Effective

H1N1 flu virus may be “direct descendant” of the 1918 influenza strain

- Red Yeast Rice Scare Grips Japan: Over 114 Hospitalized and 5 Deaths

- Long COVID Brain Fog: Blood-Brain Barrier Damage and Persistent Inflammation

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

H1N1 flu virus may be “direct descendant” of the 1918 influenza strain.

A study published on the 10th in the British journal “Nature Communications” found that the seasonal H1N1 influenza virus may be a “direct descendant” of the 1918 flu strain that caused the global influenza pandemic. The results come from a genomic analysis of European samples during the 1918 pandemic.

It is estimated that the 1918 influenza pandemic killed between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide. What is known about the spread and timing of the flu is based on historical sources and medical records, which show that the pandemic peaked in the fall of 1918 and continued into the winter of 1919.

However, it was not until the 1930s that it was confirmed that the source was a viral infection, after which research showed that the culprit was the H1N1 subtype of influenza A virus. Genome analysis of the 1918 virus has also been difficult to carry out due to the very few viral sequences left at the time.

Scientists from the Robert Koch Institute in Germany analyzed 13 lung samples collected in the historical archives of German and Austrian museums from different individuals, collected between 1901 and 1931, of which 6 samples were collected in 1918 year and 1919.

From these samples, they were able to sequence two incomplete genomes collected in Berlin in June 1918 and a complete genome collected in Munich in 1918.

The researchers believe that the genomic diversity of these samples is consistent with a combination of indigenous dispersal and long-distance dispersal events.

By comparing the genomes before and after the peak of the pandemic, they found differences in nucleoprotein genes that are associated with resistance to the antiviral response and may have helped the virus adapt to humans.

The research team also modeled molecular clocks, a method that can be used to estimate the time scale of evolution.

They found that all the genome segments of the seasonal H1N1 flu virus may be “direct descendants” of the initial strain of the 1918 pandemic. This refutes other hypotheses that the seasonal virus arises from genetic recombination (the exchange of genome segments from different viruses).

The researchers stress that their sample size is still extremely limited, but the study has provided further insight into the evolution and development of the 1918 influenza pandemic, which also demonstrates the invaluable value of consulting historical archives.

H1N1 flu virus may be “direct descendant” of the 1918 influenza strain

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.