BMJ: Cervical cancer screening may usher in a big change!

- Mifepristone: A Safe and Effective Abortion Option Amidst Controversy

- Asbestos Detected in Buildings Damaged in Ukraine: Analyzed by Japanese Company

- New Ocrevus Subcutaneous Injection Therapy Shows Promising Results in Multiple Sclerosis Treatmen

- Dutch Man Infected with COVID-19 for 613 Days Dies: Accumulating Over 50 Virus Mutations

- Engineered Soybeans with Pig Protein: A Promising Alternative or Pandora’s Dish?

- Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS): A Tick-Borne Threat with High Mortality

BMJ: Cervical cancer screening may usher in a big change!

- Red Yeast Rice Scare Grips Japan: Over 114 Hospitalized and 5 Deaths

- Long COVID Brain Fog: Blood-Brain Barrier Damage and Persistent Inflammation

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

BMJ: Cervical cancer screening may usher in a big change!

A study of more than one million women found that the cervical cancer screening interval of HPV-negative women was extended to 5 years or more.

Cervical cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among women worldwide, and its morbidity and mortality ranks fourth among female malignant tumors in the world [1].

Fortunately, the cause of cervical cancer is clear, preventable and curable. Although nearly all cervical cancers are caused by high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) infection, only a small percentage of hrHPV infections persist and develop into high-grade cervical lesions (eg, CIN3+) . This small group of infected individuals may eventually develop cervical cancer if left untreated [2].

In addition, cervical cancer is the only gynecological tumor that can be prevented through regular screening . Cervical cancer screening can detect HPV infection (HPV test) or cervical cell lesions (cytology test), both of which indicate the risk of cervical lesions, and those with positive screening results need to be diagnosed by pathological diagnosis.

Previous guidelines generally recommend cytology testing every 3 years for women aged 21-65 . However, in recent years, the screening program using HPV detection as the primary screening method for cervical cancer has been widely recognized. Compared with cytological testing, the HPV screening program has high detection sensitivity, and the screening interval can be longer [3].

Recently, a research team led by Matejka Rebolj of King’s College London , UK, published a blockbuster research result in the famous journal “British Medical Journal” (BMJ).

Based on the data from the UK HPV testing pilot study, they found that the 3- or 5-year risk of cervical lesions in HPV-negative women of all ages was lower than that of cytology-negative women, and the risk assessment results were not affected by HPV testing methods [4].

The study pointed out that the cervical cancer screening interval for HPV-negative women aged 24-49 was extended to 5 years, and the screening interval for HPV-negative women over the age of 50 could even be extended to more than 5 years .

The results of previous randomized trials have shown that, compared with cytological testing, HPV testing has higher sensitivity and higher negative predictive value for the detection of cervical lesions [3], which means that the proportion of cervical lesions and cervical cancer in the population with negative HPV testing is lower.

Based on this characteristic, experts recommend extending the screening interval for HPV-negative women, and some screening programmes (eg, those in England, Scotland, and Wales) have announced plans to extend the screening interval for HPV-negative women in certain age groups [4].

However, due to the small sample size of the previous randomized trials, the clinical manifestations of different HPV detection methods and women of different age groups were not evaluated separately, and fewer HPV detection methods were involved (only HC2 and GP5+/6+-PCR were included). method) , it has not been possible to assess whether a protocol for prolonging the interval between cervical cancer screening in HPV-negative women is applicable to all HPV testing methods and women of all ages [3].

Therefore, clinical trials with larger sample sizes involving different HPV detection methods are urgently needed to assess the risk of cervical lesions in women with negative HPV screening at different ages, and to provide a basis for clinical application .

The data for this study are derived from the UK HPV screening pilot study, which was completed by six different laboratories in collaboration, including two rounds of cervical cancer screening.

The first round of screening was carried out from May 2013 to December 2016.

A total of 1,341,584 women of school age were screened, of which 403,883 were tested for HPV and 937,701 were tested for cytology.

HPV detection methods include detection of HPV mRNA (APTIMA) and detection of HPV DNA (cobas or RealTime).

Number of people and detection methods included in the first round of screening for each laboratory

Women participating in screening were triaged based on the results of the first round of screening.

For women with positive screening results and eligible for colposcopy referral, colposcopy and pathological diagnosis were performed.

For those with negative screening, the second round of screening should be carried out 3 years or 5 years after screening according to the age of the screener: 24-49 years old with negative screening, the second round of screening will be carried out after 3 years, 50-59 years old Those aged 60-64 underwent a second round of screening after 5 years, and those aged 60-64 did not undergo a second round of screening.

Those who were positive in the second round of screening were also subjected to colposcopy and pathological diagnosis.

In addition, the incidence of cervical cancer and CIN3 from 1995 to 2018 was obtained from the UK National Cancer Registry and Analysis Service.

Based on the results of the two rounds of screening, the risk of CIN3+ or cervical cancer was compared between those with negative HPV tests and those with negative cytology tests.

To help formulate policy recommendations, this study assumes that the 3- or 5-year risk of CIN3+ or cervical cancer in cytology-negative individuals represents a clinically acceptable risk, and that HPV-negative individuals have screening intervals similar to their corresponding cervical disease risk. Screening interval for negative cytology.

In short, the current recommended screening interval for women aged 24-49 years with negative cytology is 3 years.

Assuming that the risk of CIN3+ or cervical cancer corresponding to the 5-year interval of HPV-negative persons aged 24-49 is consistent with the risk of CIN3+ or cervical cancer of the 3-year interval screening of cytology-negative persons in this age group, then the screening rate of HPV-negative persons aged 24-49 years is the same. The inspection interval can be set at 5 years .

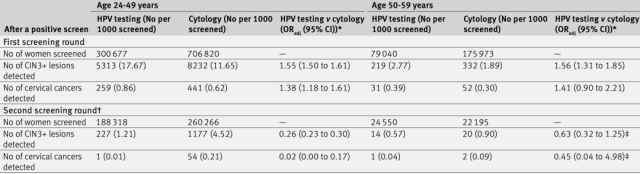

The results of the study found that compared with cytological testing, HPV testing has higher sensitivity for CIN3+ or cervical cancer detection, and the proportion of CIN3+ and cervical cancer detected in the first round of HPV testing in the 24-59-year-old HPV testing population was higher .

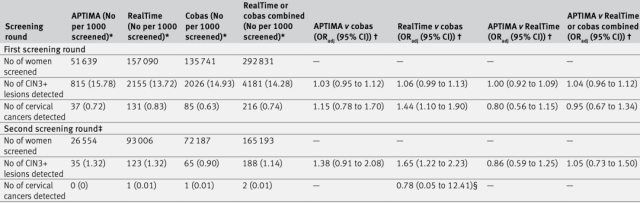

Results of two rounds of cervical cancer screening for women aged 24-59

Conversely, in the second round of screening of screen-negative individuals, HPV-negative 24-59-year-olds had a lower risk of both CIN3+ and cervical cancer than cytology-negative individuals.

The detection rate of CIN3+ in HPV-negative women aged 24-49 years was 74% lower than that in cytology-negative women (1.21/1000 vs 4.51/1000, OR=0.26, 95% CI=0.23-0.30) .

Furthermore, HPV-negative individuals also had a lower risk of cervical cancer between screening rounds than cytology-negative individuals.

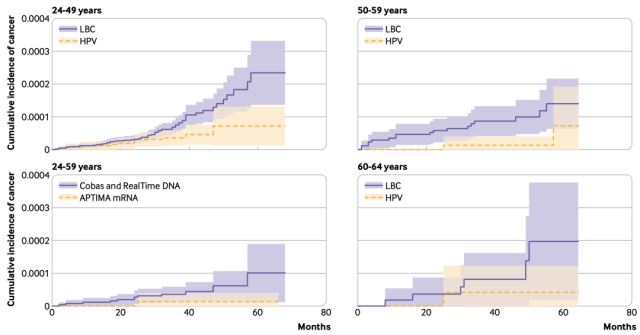

The figure below shows the cumulative incidence of cervical cancer during the screening period for women who were negative in the first round of screening.

From the figure, it can be seen that the 5-year cumulative incidence of cervical cancer in HPV-negative women of all ages is higher than that of women with negative cytology tests.

The 3-year cumulative incidence of cervical cancer was lower. According to the principle of equal risk equal management, the screening interval for HPV-negative women can be extended to 5 years.

Cumulative cervical cancer incidence between screenings among women with negative first-round screening (by age group or screening method)

In addition, the results of this study showed that HPV-negative women over the age of 50 had a lower risk of CIN3+ than women aged 24-49: HPV-negative women aged 50-59 had a 5-year CIN3+ detection rate compared with HPV-negative women aged 24-49. The CIN3+ detection rate was also about 50% lower (0.57/1000 vs 1.21/1000).

These results support extending the screening interval for HPV-negative individuals.

That is, the screening interval for HPV-negative persons under the age of 50 can be extended to 5 years, and the screening interval for persons over 50 years old can be extended to more than 5 years .

About 50% to 90% of women infected with HPV will turn negative within 1-2 years.

So is it possible to extend the screening interval to 5 years or more for the initial HPV-positive women who are automatically negative?

The answer is negative.

The results of this study found that compared with the initial HPV-negative women, HPV-positive women who turned negative between two screening rounds had a higher proportion of CIN3+ detected in the second round of HPV screening (5.39/1000 vs 1.21/1000, OR=3.27, 95% CI=2.21-4.84).

The screening interval of 3 years should continue to be maintained for this population.

The study also assessed the risk of CIN3+ or cervical cancer in HPV-negative individuals with different HPV testing methods.

The results showed that HPV mRNA-based detection (APTIMA) and HPV DNA-based detection (cobas or RealTime) had basically the same detection rates for CIN3+ and cervical cancer in the first and second rounds of detection.

It shows that the scheme of prolonging the interval of cervical cancer screening for HPV-negative patients is suitable for different HPV detection methods .

Comparison of results of different HPV screening methods

Overall, this study was conducted in the real-world setting of the UK National Screening Program, and the detection and diagnostic methods used in the study were consistent with routine screening, which would facilitate wider dissemination of the findings .

In addition, the large number of women included in this study, several times larger than the randomized trials that underpin the widespread use of HPV testing [3], provides more data on screening and diagnosis in later stages of negative cervical cancer screening.

The influence of different HPV detection methods on the screening results was also evaluated, which provided an important basis for extending the cervical cancer screening interval for HPV-negative women of all ages .

However, this study also has some shortcomings. For example, the number of women with cancer observed in specific low-risk subgroups (such as older women with negative screening in the first round) remains low; data from early recalls in the second round are scarce, especially for 50-59 year olds female. These could all affect the statistical results of the study.

In addition, this study did not address self-sampling HPV testing, and it has not been possible to assess whether a protocol for extending the cervical cancer screening interval for HPV-negative women is applicable to this increasingly popular cervical cancer screening sampling protocol .

Because the sensitivity of self-sampling HPV testing for cervical lesions is comparable to that of physician sampling [5], it can avoid the embarrassment of physician sampling, and is not limited by sampling time and location, so women of different ages, races and nationalities The acceptance is relatively high [6-9].

For example, some countries’s “China Multicenter Screening Test (CHIMUST) [10]”, “Shenzhen Cervical Cancer Screening Test 2 (SHENCCAST-2) [11]”, “China Cervical Cancer Prevention Study (CHIPCAPS) [12]”, “Pingshan Project [13]” and “Xinxiang Project [14]” have self-sampling HPV testing.

Therefore, future evaluation of the screening interval of self-sampling HPV testing will help to optimize the cervical cancer screening management plan on a larger scale and obtain better economic benefits .

references:

1. Sung, H., et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021. 71(3): p. 209-249.

2. Schiffman, M., et al., Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet, 2007. 370(9590): p. 890-907.

3. Ronco, G., et al., Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet, 2014. 383(9916): p. 524-32.

4. Rebolj, M., et al., Extension of cervical screening intervals with primary human papillomavirus testing: observational study of English screening pilot data. Bmj, 2022. 377: p. e068776.

5. Arbyn, M., et al., Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. Bmj, 2018. 363: p. k4823.

6. Racey, CS, et al., Randomized Intervention of Self-Collected Sampling for Human Papillomavirus Testing in Under-Screened Rural Women: Uptake of Screening and Acceptability. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2016. 25(5): p. 489-97.

7. Mullins, R., K. Scalzo, and F. Sultana, Self-sampling for cervical screening: could it overcome some of the barriers to the Pap test? J Med Screen, 2014. 21(4): p. 201- 6.

8. Tiro, JA, et al., Understanding Patients’ Perspectives and Information Needs Following a Positive Home Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling Kit Result. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2019. 28(3): p. 384-392.

9. Sultana, F., et al., Women’s experience with home-based self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing. BMC Cancer, 2015. 15: p. 849.

10. Song, F., et al., The effectiveness of HPV16 and HPV18 genotyping and cytology with different thresholds for the triage of human papillomavirus-based screening on self-collected samples. PLoS One, 2020. 15(6): p. e0234518.

11. Wu, R., et al., Secondary screening after primary self-sampling for human papillomavirus from SHENCCAST II. J Low Genit Tract Dis, 2012. 16(4): p. 416-20.

12. Belinson, JL, et al., The development and evaluation of a community based model for cervical cancer screening based on self-sampling. Gynecol Oncol, 2014. 132(3): p. 636-42.

13.Du, H., et al., The prevalence of HR-HPV infection based on self-sampling among women in China exhibited some unique epidemiologic features. J Clin Epidemiol, 2021. 139: p. 319-329.

14. Song, F., et al., Evaluation of p16(INK4a) immunocytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping triage after primary HPV cervical cancer screening on self-samples in China. Gynecol Oncol, 2021. 162(2): p 322-330.

BMJ: Cervical cancer screening may usher in a big change!

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.