How to treat malignant rock slope area tumors?

How to treat malignant rock slope area tumors?

How to treat malignant rock slope area tumors? Treatment strategies for brain tumors in difficult petroclinic areas.

The management of malignant rock slope tumors requires a multidisciplinary team. Family doctors, neurologists, or ophthalmologists usually determine the tumor based on the patient’s initial presentation, because the most common symptom is diplopia. This is usually caused by impaired function of the cranial nerve VI, shortly after the nerve passes through petrosine to join the cartilage.

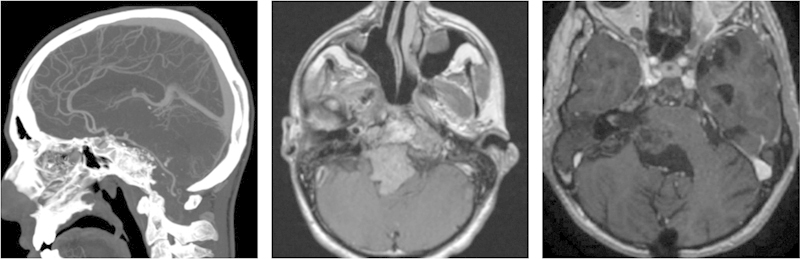

Their surgical treatment is challenging, forcing multiple specialties involved to achieve satisfactory tumor resection with negligible or no morbidity. The surgical plan begins with neuroradiologists studying and describing the internal characteristics of the tumor and its relationship with important neurovascular structures. Medical professions, including internal medicine and endocrinology, should also evaluate patients before surgery to optimize their surgical conditions.

Otolaryngologists, head and neck surgeons, neuro-ophthalmologists and neurosurgeons represent the core surgical team. Ideally, the surgical team should be proficient in various open, endoscopic and microscope methods of skull base surgery. The latter parameter is important because the surgical strategy must be individualized for each patient, and the approach (or approach) customized to minimize damage to normal tissues, so as to preserve or restore function. In addition, the surgical treatment of these tumors requires in-depth anatomical knowledge and team experience.

After the operation, another group of professionals concerned about the patient’s recovery and rehabilitation. During this period, neuro-enhancement doctors and rehabilitation doctors, as well as nurses, physical therapists, speech pathologists, occupational therapists and social workers all played important roles. Once the patient recovers from the stress of surgery, medical and radiation oncologists become the center to develop and implement the best long-term disease control strategy.

Anatomy of the skull in the petroclinic area

Slope, which means “slope” in Latin, is part of the occipital bone. It extends downward from the back of the saddle to the foramen magnum. The top and front edges of the slope form a joint with the saddle back and define the top and front edges of the posterior fossa. The slope has a unique anatomical relationship with the sphenoid bone. It is located behind and below the sphenoid sinus and can be accessed through transsphenoidal and nasopharyngeal approaches.

The petrous part of the temporal bone is wedged into the middle of the skull base, the front edge is the squamous part of the temporal bone and sphenoid bone, and the posterior edge is the occipital bone. Its front surface forms the edge of the middle cranial fossa, and its back surface forms the edge of the posterior fossa.

Tumors that spread from slopes and rock slopes can affect several key neurovascular elements, including the anterolateral surface of the pontine, the basilar artery and its branches, and cranial nerves III to XII. The clava dura is unique because of its double-layer structure, abundant basal venous plexus and abundant surrounding sinus-like venous system. Tumors in this area can displace, swallow and even infiltrate these structures, showing important clinical morphologies. These morphologies should be identified before surgery to determine the most appropriate surgical approach.

The most commonly affected cranial nerve is the sixth nerve, which is closely related to the combined cartilage of the rock slope. The cranial nerve VI passes through the subarachnoid space, through the meningeal layer of the dura mater, immediately behind the petroclinic combined cartilage and then walks in the dural cavity, and then between the meningeal layer and petroclinal periosteum, to the upper and outer side of the Dorello canal Direction. In this area, the cranial nerve VI shares the space with the inferior petrosal sinus and is most vulnerable to damage from the petroclinic area.

Surgical planning and decision making

As a multidisciplinary team to implement the global management of malignant petroclinic tumors, it is important for all participating processes to determine the strategic plan of treatment in a timely manner. All skull base cases should be discussed at the meeting until the radiologist, neuro-oncologist, neurosurgeon, otolaryngologist, head and neck surgeon, and radiation oncologist agree on the surgical approach and overall treatment. The initial decision must take into account the goals of treatment and the need for surgical intervention.

As mentioned earlier, some patients with tumors that have metastasized to the base of the skull may have disseminated systemic disease. The initial assessment may be to determine whether palliative care is needed. In other cases, a diagnosis may be required to determine the best treatment route without the need to remove the tumor. Examples of malignant tumors of rock slopes are lymphoma, plasmacytoma and metastases.

Once surgical treatment is determined as the best primary treatment, the team should jointly decide how to maximize the removal of the tumor while avoiding vascular damage, while minimizing the need for cranial nerves or nerve tissue to be displaced or constricted. With this in mind, when complex multi-chamber tumors appear, patients can be provided with intranasal or transcranial access, or a combination of both.

Skull base surgeons can use multiple methods to approach lesions in rocky slopes. Taking into account the complex local neurovascular structure, the anteromedial (intranasal path), anterolateral (orbitozygomatic approach and petrosotomy), and lateral (anterior-posterior through the sigmoid sinus) are formulated to reach the area. Petrotomy) and posterior (post-mastoid sigmoid approach) trajectories; each method has its limitations and advantages.

Generally speaking, the endoscopic lumen approach is an anterior internal approach, which is ideal for median lesions including the lateral slope of the left ventricle. As long as the tumor has formed a corridor, pushing important neurovascular structures to the surrounding, some tumors that extend outward can still be approached mainly through the ventral approach. Chondrosarcoma is an extremely complex tumor that starts from petrosal combined cartilage and can extend to the middle cranial fossa, posterior fossa and even the upper part of the neck. It can still be completely resected through the enlarged nasal cavity.

In this case, it is usually necessary to remove the Eustachian tube to allow complete tumor exposure and resection. Even the lateral tumor that extends to the posterior side of the internal carotid artery can be accessed from the lumen, which usually requires removal of the carotid bony tube to lateralize the ICA and better reach the posterior side. On the other hand, if the tumor extends to the outside of the cranial nerve, it is best to approach it from the outside. Ultimately, the choice of approach depends on how the tumor swallows or replaces the cranial nerves, carotid artery, and basilar artery.

Most petroclinic malignancies can be treated by endoscopic endonasal approach, which can be completely resected, or can be used as part of a multi-channel surgical strategy to target subtotal resection. When the tumor invades multiple cranial cavities (cavernous sinus, middle fossa, posterior fossa) and exceeds the level of cranial nerves, the microscopic approach should be supplemented by an open approach during the same anesthesia or the second phase of the patient’s recovery. In addition, if petroclinic tumors seem to be suitable for total resection through an open method in a single stage, then the multidisciplinary team should also consider this and choose a less pathological alternative.

When approaching a patient with a petroclinic mass, we should first pay attention to the treatment goals and the need for surgical intervention. Generally, diagnosis needs to be performed while limiting the morbidity and maintaining the patient’s neurological status and quality of life. The treatment plan should be adjusted according to the natural history of the disease and the individual comorbid conditions of the patient.

If surgery is required, the patient may need single-stage or multiple-stage surgery to achieve total resection while minimizing nerve damage. Adjuvant treatment is usually required. Although chemotherapy may play a role in specific cases, radiotherapy is a consistent part of a multimodal treatment model. The joint efforts of doctors from multiple specialties is essential to ensure the best possible results.

(source: chinanet)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org