Cracking the Code of Long COVID Fatigue: New Insights from Recent Research

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Cracking the Code of Long COVID Fatigue: New Insights from Recent Research

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Cracking the Code of Long COVID Fatigue: New Insights from Recent Research

Feeling constantly tired and fatigued after recovering from COVID-19? The latest research in the Nature Communications journal has identified the reasons behind the persistent fatigue in “long COVID” patients!

As the year-end approached, the JN.1 variant of the COVID-19 virus spread globally, once again bringing the “COVID-19 pandemic” into the spotlight.

In August 2023, JN.1 was first discovered in Luxembourg, Europe. With over 30 spike protein mutations and stronger immune evasion capabilities, JN.1 rapidly spread worldwide.

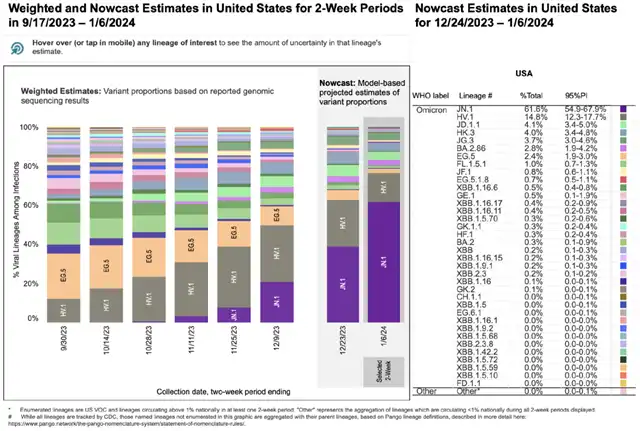

The latest statistics in the United States as of January 6, 2024, reveal that in the past two weeks, the new variant JN.1 has surged ahead, accounting for 61.6% of all new COVID-19 cases in the country, surpassing the previous variant HV.1. Concurrently, hospitalizations and deaths have increased by 20.4% and 12.5%, respectively.

However, the impact on the United States is not solely from the new COVID-19 variant; the “triple threat” of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza has added significant pressure to hospitals. Health experts also warn that the U.S. is grappling with the most severe winter season they have ever seen.

CDC monitors the proportion of new COVID-19 variant strains in the U.S.

The first wave of the new COVID-19 infection hit Singapore in this round. In just one week (December 3-9), Singapore reported a staggering 56,043 new infections, approximately 1% of the total population. Aside from the sharp increase in weekly infections, hospitalizations and intensive care cases have also risen during the same period.

Dr. Leong Ho Nam, an infectious disease specialist in Singapore, emphasizes that this current wave of infections is “more than twice as bad” compared to when the Omicron variant first appeared. However, the disclosed data is just the “tip of the iceberg.” To alleviate the strain on healthcare, Singapore has reopened “field hospitals” and resumed daily pandemic reporting.

Turning to China, according to data from the National Bioinformatics Center, JN.1 was reported in Shanghai on October 11 this year. A spokesperson at the press conference by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention stated, “The JN.1 variant currently has a relatively low proportion, but it is on the rise and could gradually become a prevalent strain domestically.” Vigilance and infection prevention are still crucial.

In fact, after successive waves of infections, the likelihood of the COVID-19 virus becoming more virulent is relatively low. The reported symptoms of JN.1 infection, including common ones like fever, cough, difficulty breathing, fatigue, muscle aches, runny nose, diarrhea, and severe headaches, have not shown new or more severe symptoms.

Therefore, the more concerning issue remains the long-term effects of COVID-19 on individuals – the post-COVID syndrome or “long COVID.”

“Long COVID” has been a recurring issue, but with the continuous cycle of “positive-negative-recovery,” many people have personally experienced the power of long COVID. For example, after recovery, individuals may feel more prone to fatigue and weakness, especially for those who enjoy physical activities. After recovering from COVID-19, resuming exercise or fitness routines may lead to increased fatigue and overall body soreness.

What is the underlying cause behind this? What kind of “heavy blow” has the body experienced?

A recent study published in Nature Communications sheds light on the pathological physiology of reduced exercise capacity and post-exertional malaise (PEM) in long COVID patients.

After infection with the COVID-19 virus, the skeletal muscle structure of long COVID patients undergoes changes, including local and overall metabolic disruptions in the skeletal muscles, severe exercise-induced myopathy, and tissue infiltration with amyloid-like protein deposits, exacerbating PEM.

This study provides a rational explanation for the “persistent fatigue after recovery” symptoms in long COVID patients.

It also serves as a warning to those who love sports and fitness: it is not advisable for long COVID patients to engage in excessive exercise, and moderation is key.

Strengthening exercise may worsen symptoms, and some commonly used rehabilitation and physical therapy methods may have counterproductive effects.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-44432-3

Previously collected data indicates that limited exercise endurance and post-exertional malaise (PEM) are common symptoms of long COVID, with fatigue and pain-related symptoms intensifying after acute mental or physical activity. However, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms were not clear.

To identify the “culprit,” researchers first collected data from 25 “long COVID” patients. These patients, diagnosed by two experienced clinicians according to the World Health Organization’s criteria for “long COVID,” also had “PEM diagnosed by DSQ” as another important inclusion criterion. Additionally, 21 participants who had fully recovered from mild COVID-19 infection and matched in age and gender with the former group were included as a control.

The results were not surprising. Compared to the control group, long COVID patients showed poorer performance in cardiopulmonary exercise tests, indicating limited exercise capacity.

Specifically, long COVID patients exhibited significantly lower maximal oxygen consumption (V̇O2max) and peak power output. They also had lower maximum ventilation and end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure (PETCO2), indicating poorer ventilatory function during exercise.

Where is the problem? Is it damage to the cardiovascular system, or has there been a change in skeletal muscles?

In fact, the cardiovascular system of long COVID patients remained undamaged, ruling out that factor. Further investigations revealed that, during exercise, long COVID patients experienced a decline in indicators such as maximum oxygen pulse, gas exchange threshold, and peripheral oxygen extraction levels, suggesting damage to the peripheral skeletal muscles.

Having identified the skeletal muscles, researchers further assessed changes in their structure and function, attempting to find the “key” to unlocking the “Pandora’s box.”

Under conditions where skeletal muscle size was controlled, long COVID patients could not achieve the same peak power output as the healthy control group. Thus, the decline in the exercise performance of patients could be partially attributed to intrinsic changes in skeletal muscle strength and fatigue characteristics.

Furthermore, researchers found a significantly higher proportion of highly fatigable glycolytic fibers in the lateral thigh muscles of long COVID patients compared to the healthy control group. Particularly in female long COVID patients, there was even observed a smaller cross-sectional area of fatigue-resistant type I fibers.

In addition, in the healthy control group, the marker of mitochondrial content – succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity – showed a strong correlation with V̇O2max. However, in long COVID patients, these two factors were not correlated. Although oxidative phosphorylation capacity in long COVID patients was significantly lower, SDH activity did not change. This suggests a decrease in the quality of mitochondrial respiration, rather than a reduction in mitochondrial enzyme activity.

The data above indicates that the potential reasons for the decreased exercise capacity in long COVID patients include a higher proportion of highly fatigable glycolytic fibers and lower mitochondrial function in skeletal muscles. Lower capillarization and ventilatory system function may also contribute to some limitations.

Furthermore, researchers observed and summarized the pathological physiology of PEM, which includes several aspects:

-

Reduction in maximum mitochondrial respiration and decreased mitochondrial content: Researchers measured mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscles before and after inducing PEM and found that SDH activity in long COVID patients was significantly lower than in the healthy control group.

-

Accumulation of amyloid-like protein deposits in skeletal muscles: At baseline, the concentration of amyloid-like protein deposits in the skeletal muscles of long COVID patients was higher, and it increased significantly after exercise.

-

Signs of severe muscle tissue damage: A significant portion of long COVID patients showed signs of small atrophic fibers and focal necrosis, which increased noticeably after exercise. Additionally, skeletal muscles are a plastic tissue, and signs of muscle regeneration were more apparent in long COVID patients. This explains the muscle pain, fatigue, and weakness experienced by long COVID patients during PEM.

-

Exercise-induced T-cell response blunting: Observation of immune cells revealed the infiltration of CD68+ macrophages in the skeletal muscles of long COVID patients. Furthermore, exercise led to the accumulation of CD3+ T cells in muscle tissue, but this response was weakened in PEM patients.

In summary, reduced exercise capacity is one of the hallmarks of long COVID, bringing a heavy burden to the daily lives of patients. Through comparison and exclusion, researchers identified the pathological physiological abnormalities in the skeletal muscles – specifically, the decreased exercise capacity of long COVID patients is mainly due to changes in skeletal muscle metabolism and an increase in highly fatigable glycolytic fibers. After intense exercise, post-exertional malaise worsens, involving reduced mitochondrial enzyme activity and signs of muscle tissue damage.

As the corresponding author pointed out, the fatigue symptoms in long COVID are due to biological changes. Muscles need energy to function, and from a cellular perspective, the decrease in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and energy production under the shadow of the COVID-19 virus inevitably leads to reduced exercise capacity and more intense post-exertional malaise.

Therefore, I would like to remind everyone: take a gradual approach to exercise after recovering from COVID-19, as your muscles may not have fully recovered from the shadow of the virus, so avoid overexertion at all costs.

Cracking the Code of Long COVID Fatigue: New Insights from Recent Research

References:

[1]Appelman B, Charlton BT, Goulding RP, Kerkhoff TJ, Breedveld EA, Noort W, Offringa C, Bloemers FW, van Weeghel M, Schomakers BV, Coelho P, Posthuma JJ, Aronica E, Joost Wiersinga W, van Vugt M, Wüst RCI. Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nat Commun. 2024 Jan 4;15(1):17. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44432-3. PMID: 38177128; PMCID: PMC10766651.

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.