Parkinson Disease and Sleep Disorders

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Parkinson’s disease and sleep-wake disorders

Parkinson Disease and Sleep Disorders. Sleep disorders related to Parkinson’s disease: rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD), restless legs syndrome (RLS) and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).

In this issue, Shuer shares an article titled “Parkinson’s Disease and Sleep/Wake Disturbances” published by Keisuke Suzuki et al. in 2015 on Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.

Summary

Sleep disturbance is a common non-motor feature in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Early diagnosis and proper management are essential to improve the quality of life of patients.

In addition to age-related sleep changes, sleep disorders may also be caused by a variety of factors, such as nocturnal motor symptoms (stiffness, resting tremor, dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and “fatigue” phenomenon), non-motor symptoms ( Pain, hallucinations and psychosis), nocturia and medication.

Disease-related pathology involving the brainstem and changes in the neurotransmitter system (norepinephrine, serotonin, and acetylcholine) responsible for regulating sleep structure and sleep/wake cycle play a role in the occurrence of excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep disorders.

In addition, screening for sleep apnea syndrome, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and restless legs syndrome is clinically important.

The use of Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale-2 to conduct a questionnaire assessment is helpful for screening Parkinson’s disease-related nocturnal symptoms. In this review, we will focus on the current understanding and management of sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

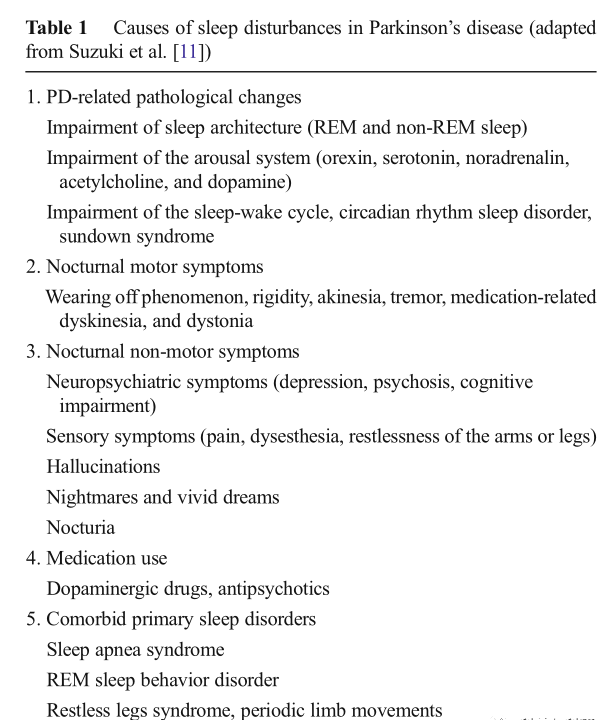

Sleep disturbance is a common disabling non-motor feature of Parkinson’s disease, which has an adverse effect on health-related quality of life. The causes of sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease are multifactorial and overlapping (Table 1). According to reports, the prevalence of sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease patients varies with the study population and methods, and the value range is about 40% to 90%.

The frequency of sleep disorders increases with the progression of the disease, reflecting the effects of night movement and non-motor symptoms on sleep; however, sleep disorders can occur at any time during sleep disorders, which may indicate the coexistence of more non-motor symptoms and Decline in the quality of life. Sleep disorders are also related to the decline in the quality of life of patients with early Parkinson’s disease.

Surprisingly, in a multicenter international study examining non-motor symptoms, about half of Parkinson’s disease patients found no sleep problems, such as insomnia and daytime sleepiness. Some Parkinson’s disease patients show improvement in exercise before waking up in the morning and before taking medication. This phenomenon is called sleep benefit and is reported in 33-55% of Parkinson’s disease patients; however, the underlying mechanism and related factors remain unclear.

Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease and investigation of its possible causes are essential to improve the quality of life of patients. This article discusses sleep disorders related to Parkinson’s disease and provides new information on primary sleep disorders that are comorbid with Parkinson’s disease, such as rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD), restless legs syndrome (RLS), and obstruction Sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).

Causes of sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease

Many factors and conditions related to Parkinson’s disease are related to sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease (Table 1). Disease-related pathological changes include impaired thalamic cortex wakefulness and degeneration of the brainstem regulation center used to maintain sleep/wakefulness and rapid eye movement sleep, leading to excessive daytime sleepiness and insomnia.

In addition, sleep structure may be altered by brainstem disease-related changes; degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and brainstem, including noradrenergic neurons in the foot and pontine nucleus and locus coeruleus, leading to rapid eye movement sleep And RBD is reduced. The loss of serotonergic neurons in the raphe nucleus is associated with a decrease in the percentage of slow wave sleep.

Sleep disorders also originate from nocturnal motor symptoms, psychiatric symptoms, dementia, drug use, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, and comorbid primary sleep disorders, such as sleep disorder syndrome, recurrent laryngeal nerve syndrome, and RBD. There is currently no definite treatment for Parkinson’s disease-related sleep disorders.

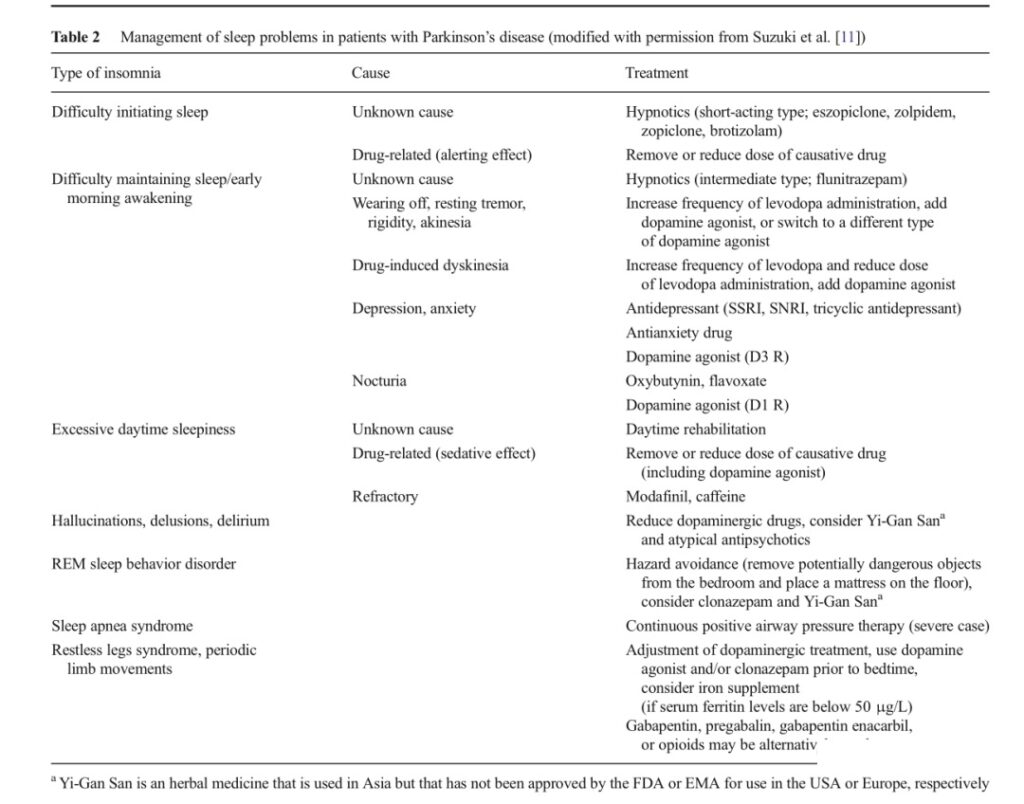

Sleep problems other than nocturnal motor symptoms, insomnia, nightmares, and dopamine dysregulation syndromes may not respond well to dopaminergic therapy; however, increase the severity of nocturnal motor symptoms, such as stiffness, bradykinesia, and resting tremor , Can benefit from increasing the dose of dopaminergic therapy at bedtime or introducing dopaminergic therapy at bedtime.

In contrast, nighttime psychiatric symptoms, including hallucinations and psychosis, can be effectively treated by reducing the dose of dopamine before going to bed or adding antipsychotic drugs. Table 2 shows the treatment methods for sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease patients.

Sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease and its relationship with the course of the disease: In patients with Parkinson’s disease, in the presence of various nocturnal motion and non-motor problems and disease-related changes in sleep structure, the estimated total sleep time and sleep efficiency Will decrease, the first and second stages of sleep will increase, and slow wave sleep will decrease.

Excessive daytime sleepiness is a common sleep problem in Parkinson’s disease. Patients with narcolepsy have reduced orexin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid. Narcolepsy is a sleep disorder characterized by daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, hypnotic hallucinations and sleep paralysis.

The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) shows a short sleep latency and rapid eye movement sleep within 15 minutes after the start of sleep, which is called the sleep onset rapid eye movement period.

In Parkinson’s disease patients, it has been observed that hypothalamic orexin levels and loss of orexin neurons are associated with disease progression. Clinically, all dopaminergic drugs have a sedative effect on patients with Parkinson’s disease.

According to reports, 3.8% to 22.8% of Parkinson’s disease patients have sudden sleep incidents while driving. In patients with higher ESS scores (≥10), the frequency of sudden sleep episodes increases [25, 27]; therefore, it is important to screen for sleep sudden events in patients with sleep disorders.

However, people should be aware that patients sometimes fail to recognize sudden sleep events.

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

01 Idiopathic RBD disease and Parkinson’s disease-related diseases are characterized by the loss of normal muscle weakness during rapid eye movement sleep and dreaming behavior. Clinical manifestations include vocalization, such as speaking and shouting, violent, aggressive and complex behaviors during REM sleep, and vivid, unpleasant, and violent dreams that can cause sleep-related harm to the patient or bed partner. There is a link between RBD disease and neurodegenerative diseases.

Observations have shown that 38% of 29 men with idiopathic RBD disease developed Parkinson’s disease 12.7±7.3 years after the onset of RBD. The 16-year update of the original study provided an 81% conversion rate of idiopathic RBD to neurodegenerative diseases (13pd; 3 Lewy body dementia (DLB); multiple system atrophy (MSA); dementia; and Alzheimer’s disease ( AD) with Lewy’s disease pathology. During the 12-year follow-up, 82% of 44 RBD patients developed neurodegenerative diseases (16 cases of Parkinson’s disease, 14 cases of DLB disease, 1 case of multiple sclerosis and 5 cases of mild Cognitive impairment).

28% of 93 patients with idiopathic RBD have neurodegenerative disease. The estimated risk of neurodegenerative disease in RBD subjects was 17.7% at 5-year follow-up and 40.6% at 10-year follow-up At 12 years of follow-up, it was 52.4%. In addition, when mild cognitive impairment was included, the risk of neurodegenerative disease in RBD patients was 33.1% at 5 years, 75.7% at 10 years, and 90.9% at 14 years.

In a clinicopathological study of 172 patients with or without neurological diseases, the neuropathological diagnosis was Lewy body disease (n=77), Lewy body disease and AD combined (n=59), MSA (n=19), AD (n=6), progressive supranuclear palsy (n=2), and others (n=9), indicating that RBD patients (n=170) associated with neurodegenerative diseases (n=170) [50 ], the proportion of synucleinopathy is higher (94%).

In summary, these longitudinal studies show that idiopathic RBD has a huge risk of synucleinopathy, especially Lewy body-related diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and DLB disease. The lack of RBD is associated with Alzheimer’s disease-like atrophy patterns on magnetic resonance imaging and increased phosphate tau load.

Subjects with idiopathic RBD have a positive family history of dreaming behavior. Potential risk factors for idiopathic RBD include comorbid depression and antidepressant use, ischemic heart disease, smoking, and head injury , Pesticide exposure and agriculture.

The involvement of cholinergic and monoaminergic brainstem nuclei, including the pontine nucleus, dorsal tegmental nucleus, dorsal inferior nucleus, and locus coeruleus, and neuronal networks involving the limbic system and neocortex are believed to contribute to RBD The occurrence of the disease.

Patients with RBD can recall the content of their dreams when they woke up when the abnormal behavior occurred, although the details may be forgotten at noon the next day. It is also worth noting that in patients with severe sleep apnea syndrome, apnea-induced arousal can mimic the symptoms of RBD.

Patients with idiopathic RBD show clinical features and abnormal test results, including olfactory disorders; visual color disorders; subtle signs of movement; increased systolic blood pressure after standing; cognitive disorders such as attention, executive function, learning ability, and vision Defects in spatial ability; cardiac autonomic dysfunction, including reduced inter-beat heart rate variability and ingestion of cardiac MIBG scintillation imaging; and substantia nigra congestion.

In a follow-up positron emission tomography study of an idiopathic RBD patient, except for a slight decrease in the left posterior putamen 1 year after the onset of RBD symptoms, the substantia nigra striatum presynaptic dopaminergic function was almost normal, but in 3.5 years after the onset of RBD, the annual reduction is 4-6%.

In a 2.5-year follow-up study of 43 subjects with idiopathic RBD, 8 of all subjects with reduced striatal dopamine transporter uptake and/or substantia nigra congestion at baseline Participants developed neurodegenerative diseases (5 cases of Parkinson’s disease, 2 cases of DLB disease, and 1 case of multiple sclerosis), but subjects with idiopathic RBD with normal neuroimaging results at baseline remained disease-free.

Before idiopathic RBD appeared clinically obvious Parkinson’s disease, 2 years before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale exercise score> 4 can predict the sensitivity of pre-Parkinson’s disease is 88%, specific The sex rate is 94%, and other quantitative exercise tests can detect Parkinson’s disease earlier. In a cross-sectional study, subtle gait changes, increased inter-stride variability, and decreased rhythm and speed were detected in patients with idiopathic RBD, which may predict early signs of Parkinson’s syndrome.

The frequency of RBD in patients with Parkinson’s disease is 15-60%, and RBD symptoms change over time. When paroxysmal nocturnal tachycardia is used for diagnosis, the frequency of RBD will increase because paroxysmal nocturnal tachycardia can detect mild RBD and abnormal behaviors that the patient does not remember when they wake up. In as many as half of Parkinson’s disease patients, RBD precedes the performance of Parkinson’s disease.

Compared with the non-group Parkinson’s disease patients, the non-previous subgroup has significantly higher scores on the first part of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Score Scale, lower quality of life scores, and lower REM apnea-hypopnea index.

Compared with the RBD non-advanced group, the RBD-advanced group has a higher age of onset of Parkinson’s disease, a shorter duration of Parkinson’s disease, and a lower levodopa equivalent dose. The comorbidity of RBD in patients with Parkinson’s disease is related to different characteristics of Parkinson’s disease, including non-motor rigidity phenotype, increased frequency of falls, poor response to dopaminergic drugs, orthostatic hypotension, and impaired color vision.

Mild cognitive impairment was found in 50% of idiopathic RBD patients and 73% of patients with RBD Parkinson’s disease, while 11% of patients with Parkinson’s disease without RBD and 8% of mild cognitive impairment control subjects Mild cognitive impairment was observed among the patients. In patients with idiopathic RBD disease and patients with RBD disease, the appearance of mild cognitive impairment increases. RBD is related to mild cognitive impairment in patients with drug-sensitive Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s disease patients with RBD disease have more severe stages, worse sleep quality, and more frequent daytime sleepiness than patients without RBD disease. RBD in patients with Parkinson’s disease is also associated with poor quality of life, and increased frequency of non-motor symptoms such as depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

Studies have shown that compared with Parkinson’s disease patients without RBD and healthy volunteers, RBD patients have lower signal intensity in the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus area, and the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus area is involved in tension control during REM sleep. .

Restless legs syndrome

RLS is a sensory motor disorder characterized by unpleasant sensations in the legs. The four basic criteria include the urge to move the legs, the onset or worsening of symptoms during rest or inactivity, relief through exercise, and predominantly occurring at night or night rather than during the day. In addition, the impact of RLS on daytime functions and sleep problems has been added to the latest ICSD-3.

However, these recurrent laryngeal nervous system standards are applicable to the general population, and there are currently no recurrent laryngeal nervous system standards for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Due to the dopaminergic dysfunction observed in the two diseases and the good response to dopaminergic drugs, the age of onset of Parkinson’s disease in both old and young is associated with RLS comorbidities.

The report studies 61% of RLS-positive Parkinson’s disease patients, symptoms related to the urge to move legs and unpleasant feelings are related to fatigue. Many Parkinson’s disease patients suffer from motor agitation and sensory symptoms associated with Parkinson’s syndrome; these symptoms may be similar to the recurrent laryngeal nervous system, and dopaminergic treatment of Parkinson’s disease may expose the subclinical recurrent laryngeal nervous system.

Two studies found that the prevalence of the recurrent laryngeal nervous system in patients with Parkinson’s disease did not increase significantly.

Sleep apnea synthesis Compared with the non-snoring control group, habitual snorers with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) less than 5 have more frequent daytime sleepiness. Among subjects with an AHI index ≥5, 22.6% were women and 15.5% were women. Of men report frequent drowsiness. In patients with Parkinson’s disease, upper airway dysfunction associated with Parkinson’s syndrome during sleep may lead to snoring and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Compared with the control group, the frequency of snoring in Parkinson’s disease patients may be higher. Compared with the healthy control group, OSA is not common in Parkinson’s disease patients. 15-40% of Parkinson’s disease patients report moderate to severe The prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (AHI≥15). Patients with Parkinson’s disease do not often experience central sleep apnea. Compared with 50 hospitalized controls (27 vs. 40%), 100 Parkinson’s disease patients (50 unselected patients and 50 patients referred for sleepiness) had a higher incidence of sleep disordered breathing (AHI> 5) low.

In addition, in the Parkinson’s disease group, sleep apnea was not associated with daytime sleepiness, nocturia, depression, cognitive impairment, or cardiovascular events. Another study studied the frequency and severity of OSA in 55 Parkinson’s disease patients, and compared them with the large sample standard data of the Sleep Heart Health Study (n=6, 132), and found that the risk of OSA in Parkinson’s disease patients did not increase (AHI 5–14.9, Parkinson’s disease 29.1%, control group 28.6%; AHI 15-29.9, 10.9 to 11.7%; AHI ≥30, 3.6 vs. 6.1%).

Compared with the OSA control group, mild nocturnal desaturation was observed in OSA patients, and the sympathetic response to OSA was slow; this may indicate that these autonomic disorders can protect Parkinson’s disease patients from cardiovascular disease. The severity of the disease is not generally related to the severity of OSA.

Conclusion

We review the current understanding of sleep problems in Parkinson’s disease patients. Management should consider the impact of sleep problems on sports and non-motor symptoms and quality of life.

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org