Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)

While rare, Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) remains the second most common primary malignant tumor of the liver.

In the United States, approximately 8,000 cases are diagnosed annually, comprising only 3% of gastrointestinal malignancies worldwide.

Over the past few decades, the incidence of ICC has been on the rise, with some studies indicating an annual increase of 14% since the early 1990s.

The increase in ICC incidence may be attributed to the global rise in hepatitis C infection rates and obesity-related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, known risk factors for ICC. Regional variations in ICC risk factors also exist; for example, in Eastern countries, ICC patients show a significantly higher relative incidence of liver stones, liver fluke infection, and viral hepatitis.

In contrast, in Western countries, ICC is more commonly associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis and other chronic liver diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and cirrhosis.

Currently, ICC treatment remains challenging, especially since most patients with advanced-stage disease cannot undergo curative surgical resection. Even among operable patients, achieving complete surgical clearance is difficult, leading to high recurrence rates.

As a result, systemic chemotherapy and targeted therapy for ICC have garnered significant attention. In the last decade, advances in understanding the molecular and genetic basis of ICC have changed treatment approaches.

Next-generation sequencing has revealed that the majority of ICC tumors have at least one targetable mutation, leading to numerous clinical trials investigating the safety and efficacy of novel therapies targeting tumor-specific molecules and genetic abnormalities.

While some clinical trials have shown promising results, large-scale randomized trials are still needed to further establish the potential clinical value of such treatments.

Mechanism of ICC Development

ICC is most commonly associated with chronic biliary inflammation and stasis. Thus, patients with diseases promoting chronic bile stasis and inflammation (primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver stones, liver fluke infection, chronic hepatitis, and cirrhosis) are at risk of developing ICC.

Common gene mutations associated with ICC include KRAS, BRAF, TP53, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). KRAS mutations are the most common in ICC, with varying incidence rates ranging from 8% to 53%. BRAF mutations are also prevalent, reported in 0-22% of ICC tumors. Patients with tumors harboring KRAS or BRAF mutations have a poorer median survival compared to those with wild-type tumors (13.5 months vs. 23.2 months for KRAS, 23 months vs. 34 months for BRAF).

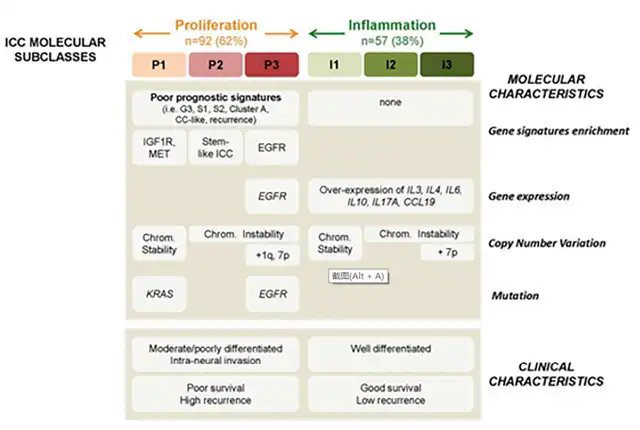

Recently, two major biological subtypes of ICC have been identified: inflammatory and proliferative. Inflammatory ICC constitutes 38% of ICC and is characterized by the activation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways through cytokines such as IL-10, IL-4, IL-6, and STAT3. Proliferative ICC, accounting for 62%, is characterized by the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways, particularly through receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK). The main types of mutations driving RTK dysfunction include gain-of-function mutations (EGFR), overexpression of RTKs and genomic amplification (EGFR, MET), chromosomal rearrangements, and constitutive activation of kinase structural domains.

Clinical phenotypes of proliferative and inflammatory ICC exhibit several important differences. Proliferative ICC tumors are more likely to be moderately to poorly differentiated, while inflammatory tumors are more likely to be well-differentiated. Survival analysis shows that patients with proliferative ICC have shorter recurrence times (15 months vs. 37 months, p=0.03) and lower median survival (24.3 vs. 47.2, p=0.048). Additionally, the incidence of KRAS mutations is 8% in proliferative ICC tumors and 7% in inflammatory ICC tumors, while BRAF mutation incidence is 5% in proliferative tumors and 2% in inflammatory tumors.

Biomarkers for ICC

The development of next-generation DNA sequencing technologies has transformed the treatment landscape for various cancers, including ICC. Up to 70% of ICC tumors may have at least one targetable gene mutation, with an average of 1 to 2 targetable mutations per examined tumor.

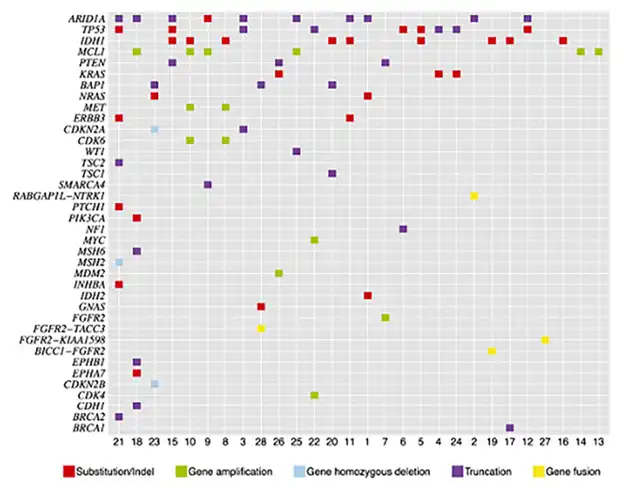

Several early studies found that the most common mutations in ICC, found in AT-rich interaction domains, include ARID1A (36%), IDH1/2 (36%), TP53 (36%), and MCL1 (21%). Common actionable mutations (for which FDA-approved drugs are available) include FGFR2 (14%), KRAS (11%), PTEN (11%), CDKN2B (7%), ERBB3 (7%), MET (7%), NRAS (7%), CDK6 (7%), BRCA1 (4%), BRCA2 (4%), NF1 (4%), PIK3CA (4%), PTCH1 (4%), and TSC1 (4%) genes.

Expression of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) has been reported in 10–70% of ICC tumor specimens, with PD-L1 positivity associated with more aggressive ICC features and poorer survival rates. Although rare, microsatellite instability (MSI) has been explored as a biomarker and target for individualized ICC treatment. Due to the rarity of MSI in ICC, conclusions about its exact incidence and prognostic impact have been challenging to draw. Current data suggest that microsatellite instability tumors (defined by the loss of DNA mismatch repair proteins MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6) are not common, occurring in a minority of ICC patients (range 1-10%).

Targeted Therapy for ICC

While various gene mutations have been identified in ICC, the incidence of many mutations remains low, posing challenges to the use of targeted therapies. However, early clinical trials have commenced for some more common gene mutations, including those involving IDH1/2, FGFR, EGFR, and VEGF gene aberrations.

IDH1/2 Mutations: Approximately 10–20% of ICC lesions harbor IDH1/2 mutations, making this gene mutation a target for therapeutic intervention. In a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial, the safety and efficacy of the mutant IDH1 inhibitor Ivosidenib were studied in patients with advanced bile duct cancer progressing on fluoropyrimidine or gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Although the trial included all types of bile duct cancer patients (i.e., intrahepatic, perihilar, distal), the majority had ICC (89% in the treatment group, 77% in the placebo group). Among 185 patients (124 in the treatment group, 61 in the placebo group), Ivosidenib was associated with improved progression-free survival (median 2.7 months vs. 1.4 months, p<0.0001) and comparable safety (30% of patients in the treatment group experienced severe adverse events vs. 22% in the control group).

Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR) Abnormalities: FGFR abnormalities are found in 10–15% of ICC tumors. FGFR is expressed in various cell types and consists of four transmembrane receptors (FGFR1-4) with intracellular tyrosine kinase domains. The binding of these FGFR receptors leads to unregulated activation of various cell proliferation pathways, including RAS-Raf MAPK, JAK-STAT, and PI3-AKT mTOR, resulting in angiogenesis and uncontrolled cell proliferation.

-

Pemigatinib: An oral kinase inhibitor inhibiting FGFR 1, FGFR2, and FGFR3. Several phase 2 clinical trials have assessed the safety and antitumor activity of Pemigatinib in advanced bile duct cancer patients with FGFR rearrangements. In one trial with 146 enrolled patients, 35% showed objective treatment responses, 42% died from disease progression, and 45% experienced severe adverse events. A phase 3, open-label, randomized, multicenter trial is currently comparing Pemigatinib with standard treatment (gemcitabine-cisplatin) for the efficacy and safety in advanced or metastatic bile duct cancer patients with FGFR2 mutations (NCT03656536).

-

Futibatinib: A selective irreversible oral FGFR 1-4 inhibitor. Its efficacy and safety were studied in a multicenter phase 2 clinical trial, where 34% of 103 enrolled patients showed objective responses, and the disease control rate was 76%. So far, 73% of patients experienced severe adverse events (≥3 grade). Another multicenter phase 3 study (NCT04093362) is comparing Futibatinib with standard treatment (gemcitabine-cisplatin).

Additionally, many other early studies are testing the safety and efficacy of mutant FGFR inhibitors.

- Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR): EGFR mutations are found in 25% of ICC tumors. EGFR is a subclass of tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptors, binding to epidermal growth factor and activating signaling pathways involved in cell movement, adhesion, angiogenesis, and invasion.

Several early trials are underway to study the safety and efficacy of EGFR and HER inhibitors (lapatinib, erlotinib, pertuzumab, trastuzumab) in patients with bile duct cancer and other solid tumors. However, significant therapeutic responses have not yet been demonstrated.

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): PD-L1 expression has been found in 10–70% of ICC tumor specimens, with its expression associated with tumor invasiveness and decreased survival rates. The safety and efficacy of several PD-L1 inhibitors have been tested in late-stage or metastatic PD-L1 positive bile duct cancer. While early trials have not conclusively demonstrated drug-related benefits, preliminary results indicate the potential effectiveness and safety of treatment.

Currently, numerous ongoing early-phase trials are testing the efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in treating late-stage MSI-ICC patients.

- BRAF Mutations: BRAF mutations occur in 5-7% of ICC cases. BRAF is a tyrosine kinase member of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway (MAPK), and BRAF mutations are associated with higher TNM staging, resistance to systemic chemotherapy, and poorer survival rates. Many studies investigating targeted therapies for BRAF-positive ICC are “basket” studies, including various types of solid tumors with BRAF mutations. Therefore, interpreting these data and identifying disease-specific efficacy has been a challenge. Currently, ongoing trials for metastatic bile duct cancer patients are underway, and results are pending.

Conclusion: Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)

In recent decades, substantial progress has been made in understanding the molecular and genetic mechanisms of ICC. This evolving knowledge has spurred the development and research of novel targeted therapies for late-stage ICC patients, some of which show significant potential correlations with disease progression and even survival.

These findings need validation through larger-scale clinical trials, and ICC patients should undergo genetic analysis to identify potential targeted therapies. Additionally, as with many rare diseases, more patients need to be appropriately involved in clinical trials to better determine the role, efficacy, and safety of targeted therapies for ICC.

Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)

Reference:

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Summative Review of Biomarkers and Targeted Therapies. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Oct; 13(20): 5169.

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.