The nucleus actually originated from a virus?

- A Single US$2.15-Million Injection to Block 90% of Cancer Cell Formation

- WIV: Prevention of New Disease X and Investigation of the Origin of COVID-19

- Why Botulinum Toxin Reigns as One of the Deadliest Poisons?

- FDA Approves Pfizer’s One-Time Gene Therapy for Hemophilia B: $3.5 Million per Dose

- Aspirin: Study Finds Greater Benefits for These Colorectal Cancer Patients

- Cancer Can Occur Without Genetic Mutations?

The nucleus actually originated from a virus?

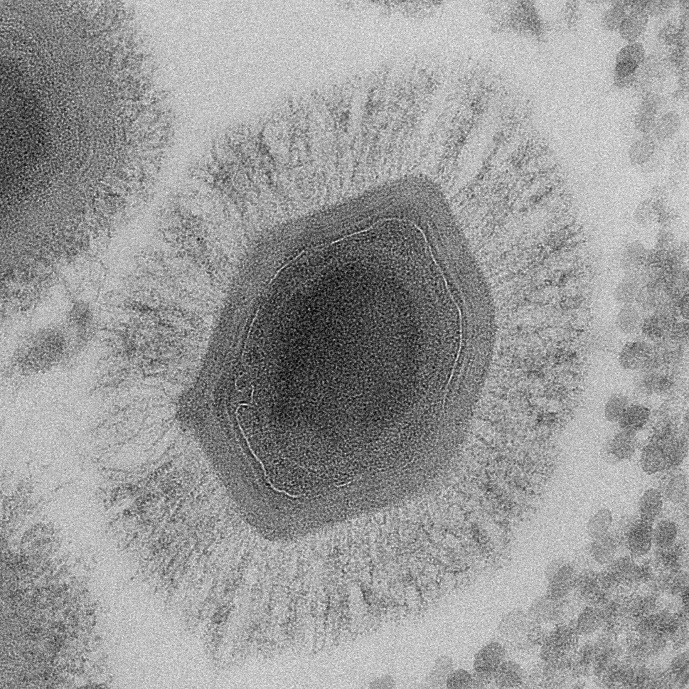

The nucleus actually originated from a virus? In the cell, a “virus factory” (the large round structure on the left in the picture) is surrounded by new virus particles (several small polygons) produced by it.

The origin of the nucleus has always been a mystery. Is its origin as strange as mitochondria? Now, there is some evidence that the cell nucleus may originate from a virus. The cell has learned how to build a virus factory and created a compartment in the cell to protect its own DNA.

Animals, plants, fungi, and protozoa have different cells, but they all have one significant feature in common: the nucleus. Although they have other organelles, such as energy-producing mitochondria, the nucleus, as a clearly distinguishable pouch-like structure containing genetic material, inspired biologist Édouard Chatton to create in 1925 The term “eukaryote” is used to refer to organisms with a “real inner core”. He called the remaining organisms “prokaryotes”, meaning “pre-nucleus” organisms. This binary classification of nucleated and non-nucleated organisms subsequently became the basis of biology.

No one knows exactly how the nucleus evolved into a key area within the cell. However, more and more evidence has led researchers to believe that nuclei, like mitochondria, may have originated in a symbiotic relationship. But the key difference is that the nucleus may not be a single cell, but a virus.

“The question of what we are, or what eukaryotes are, may be a typical case of so-called emerging complexity,” explains Philip Bell, research director at yeast biotechnology company MicroBioGen. Bell proposed the theory of virus origin in eukaryotic cell nuclei as early as 2001, and updated this theory in September 2020. “The three organisms came together to form a new community, and they merged so well that they actually formed a new life form.”

He and other researchers are more convinced of this inference from some findings. For example, they proved that cytomegaloviruses have established “viral factories” in prokaryotic cells—some compartments that resemble the nucleus, which separate transcription (reading genes). ) And translation (building protein) process. “I think this is the most convincing model right now,” he said.

Most people who study the origin of eukaryotes may disagree with his view; some still describe it as a fringe idea. But proponents of the virus origin theory point out that some recent findings can also support the model, and they believe that conclusive evidence in favor of this hypothesis is already within reach.

A gift or a scam?

Scientists generally believe that eukaryotes first appeared 2.5 to 1.5 billion years ago. There is evidence that at that time, one kind of bacteria parasitized in another prokaryotic organism, archaea, and became its mitochondria. However, the appearance of the nucleus is a bigger mystery: no one even knows whether the primitive archaea is already a nucleated proto-eukaryotic cell, or whether the nucleus appeared later .

Any theory about the origin of eukaryotic cell nuclei must be able to explain several of its characteristics. The first is its structural properties: the outer membrane of the cell nucleus and the inner membrane with a network structure composed of fibers, as well as the nuclear pores that connect its interior and other parts of the cell. In addition, there is a strange way of restricting gene expression to the inside, while leaving protein construction outside. And a truly convincing theory of origin must also explain why the nucleus exists-what evolutionary pressure caused these ancient cells to enclose their genomes?

For most of the past century, conjectures about the origin of the cell nucleus could not answer any of these questions. But at the beginning of the 21st century, two researchers independently proposed the idea that the nucleus is derived from a virus.

Masaharu Takemura, who was also a research assistant at Nagoya University at that time, became interested in the evolution of DNA polymerases (enzymes used by cells to replicate DNA) in the biochemical studies. “I performed an evolutionary phylogenetic analysis of the DNA polymerases of eukaryotes, bacteria, archaea, and viruses,” Takemura, now a molecular biology and virologist at Tokyo University of Science, recalled in an email. His analysis showed that the DNA polymerase of a class of viruses (poxvirus) is surprisingly similar to a major polymerase in eukaryotes. He speculated that this eukaryotic enzyme may have originated from an ancient pox virus.

Takemura already knows that poxviruses create a compartment in the cells they infect, where they make and replicate the virus. The combination of these facts allowed him to establish a theory: The nucleus of eukaryotic cells is produced in these primitive poxvirus compartments. In May 2001, he published the theory in the Journal of Molecular Evolution.

At the same time, in Australia, Bell also reached similar conclusions for different reasons. In the early 1990s, as a graduate student, he became interested in the theory of the origin of the cell nucleus, especially the idea that the cell nucleus, like the mitochondria, may have evolved from an endosymbiont. “I watched it for five minutes and I said, ‘oh my god, if it’s an endosymbiont, it’s not a bacterial endosymbiont,” he recalled. He felt that there are too many differences between the genomes of bacteria and eukaryotes. For example, the chromosomes of eukaryotes are linear, while the chromosomes of bacteria are often round.

But when he was studying the viral genome, he found that there are striking similarities between the genome structures of poxviruses and eukaryotes. “It took me 9 years to publish the first version of the model,” he pointed out. It then took him 18 months to publish his paper in the Journal of Molecular Evolution…but it was four issues later than Wucun’s paper.

Today, nearly 20 years later, Takemura and Bell have independently updated their hypotheses. Takemura’s revised version was published online in Frontiers in Microbiology on September 3, 2020, and Bell’s was published in Virus Research on September 20, 2020. “He is ahead of me again,” Bell said with a smile.

Both scientists cited an unusual “megavirus” recently discovered, which is one of the main reasons for their revision of the paper. When Takemura and Bell published their initial hypotheses, these viruses had not yet been discovered. Their genomes have more than one million base pairs, which are comparable in size to small, autonomously growing bacteria, and they carry genes that can code for proteins involved in the basic processes of cells. (There is some evidence that the aforementioned proteins in eukaryotic cells come from these viruses.)

But most importantly, these cytomegaloviruses replicate in complex, self-built compartments in the cytoplasm of the host cell, which is why these viruses, like poxviruses, are classified as nuclear cytomegaloviruses (NCLDVs). Patrick Forterre, an evolutionary biologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, believes that for these giant viruses, the compartments they make are “viral factories as large as eukaryotic cell nuclei.” What’s more surprising is that the virus factories produced by NCLDVs that infect eukaryotic cells also have inner and outer membranes like the nucleus. Fort Ray, Takemura, and Bell all believe that cytomegalovirus is the origin of the cell nucleus.

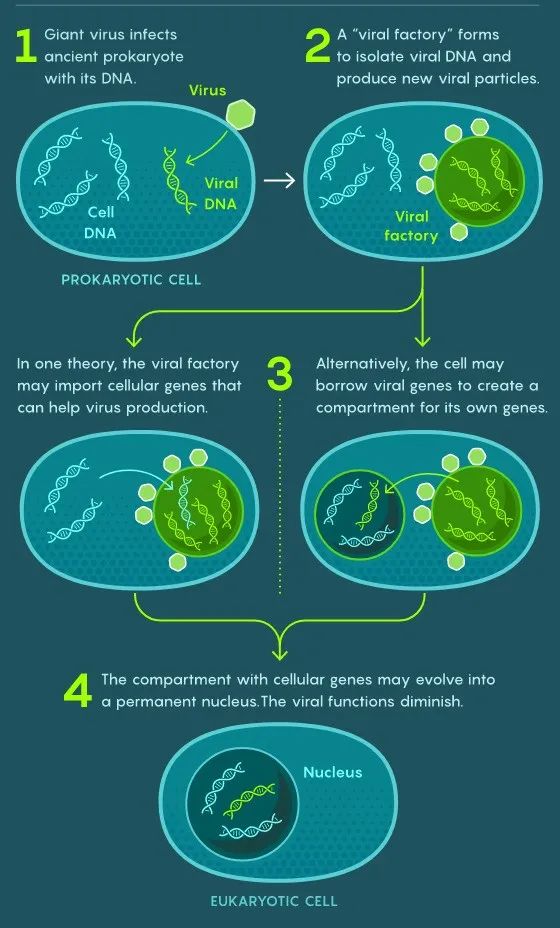

According to Fort Ray, there are two possible ways for a cytomegalovirus to evolve into a nucleus. “Either the virus factory has become a nucleus or a pro-eukaryotic cell… learn from the virus and turn itself into a virus factory to protect chromosomes,” he said.

Takemura believes that the latter is more likely: viruses are more likely to unintentionally contribute to the production of cell nuclei. It not only stimulates archaea to build barriers to protect genetic material, but also is the source of some genes needed to build barriers.

One possible way of cell origin: The virus builds a “virus factory” in the protist cell and begins to steal the host’s genes. The host has learned the “virus factory” model and built a compartment to separate its DNA from the outside world.

According to his hypothesis, a long time ago, a huge virus constructed a virus factory and closed its genome, but at the same time it also closed the genome of its host archaea. But unlike most infected cells, this host has successfully stolen the virus’ barrier building skills and built its own compartment-it can protect its genome from viruses. Over time, this semi-permanent barrier evolved into what we know as the nucleus.

Bell prefers the way that the virus factory directly becomes the nucleus, because this process is closer to the virus behavior that is now known to infect protists. “They are more like Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” he said.

He believes that the cytomegalovirus infected archaea and established a virus factory, but did not kill its host cells. On the contrary, this structure continued. “Then the virus, acting as a gene thief, stole the archaeal gene and completely destroyed its genome,” he explained. This is a common feature of viruses, especially cytomegaloviruses-they steal genes from the host, which makes them less dependent on the host. This theory may even be used to explain why so many mitochondrial genes have been transferred to the nucleus: “For many years, the nucleus has been stealing genes from the mitochondria and starting to control it.”

So to some extent, “viruses just wear archaea as overcoats,” Bell said. He pointed out that if this model is correct, “you can say that the core of every human cell is a virus.”

Controversial origin

Since the publication of Takemura and Bell’s early papers, some of the findings are consistent with the idea that the nucleus originated from a virus. For example, scientists have discovered all the branches of the cytomegalovirus family tree, broadening our understanding of their evolution, especially the important genes they exchange with their hosts—in some cases, they stole these genes and gave them back. Cell.

In addition, in 2017, researchers also discovered a virus that built a virus factory in the bacterial host. Before that, it seemed that only viruses that infect eukaryotes could make virus factories. Therefore, the discovery of viruses in prokaryotes indicates that a similar process may have occurred long ago and led to the production of cell nuclei.

In the case of the virus discovered in 2017, “this nucleus-like structure is not membrane-based,” Takemura said, which makes it different from many virus factories and eukaryotic cell nuclei. However, he still feels that viruses can build protective compartments around their genomes in prokaryotic cells, “strongly show that in ancient eukaryotic cells… the virus (probably) created the same compartment. room”.

As recently as 2020, researchers discovered pores in the double-membrane virus factory made by the coronavirus. These pores are strangely reminiscent of nuclear pores in the nucleus of a cell. David A. Baum, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote in an e-mail: “If this result is true, and it is assumed that the pore-forming protein is not derived from eukaryotes Genome, then it can indeed become the basis for responding to anti-virus models.”

However, Baum does not believe that the virus is related to the origin of the cell nucleus. For him, this idea will only make things more complicated. He wrote: “What are the difficulties in the process of cell nucleus production that need viruses to solve?”

Baum and his cousin, Buzz Baum, a cell biologist at University College London, proposed a different hypothesis: The nucleus is actually a remnant of the outer membrane of early archaea. Essentially, they believe that an early archaea began to contact the surrounding world through these exploratory membrane vesicles, and contact the bacteria. Over time, these membrane vesicles continue to grow until they fuse together again-creating new outer and inner membrane folds and spawning other intracellular compartments. “The organisms that are known to be closest to eukaryotes have extensive extracellular projections,” which interact with prokaryotes, David pointed out, “surprisingly similar to the model we proposed.”

As for some evidence that the virus gave some of the most important nuclear proteins to eukaryotes, he was most worried about the difficulty in determining the direction of this process. “Viruses are the most greedy thieves,” he said, so they keep getting genes from their hosts. “I think we have to be very careful to determine whether we have found similarities between viruses and eukaryotes. We don’t know whether they gave genes to eukaryotes or eukaryotes gave them.”

Purificación López-García (Purificación López-García), a microbial ecologist at the University of Sacré and the research director of the French National Center for Scientific Research, also does not believe that eukaryotes rely on proteins derived from viruses . She said: “There is no evidence that there is any homologous relationship between the virus, the cell and the nucleus.”

However, Lopez-Garcia also disagrees with the bubble model proposed by Baum’s cousins. She and her colleagues believe that eukaryotes did not originate from the archaea that swallowed bacteria (which later became mitochondria). On the contrary, in their view, because of the earlier symbiotic event, the archaea have lived inside a larger bacteria. “So, in our model, the nucleus is from this archaea, and the cytoplasm is from the bacteria.” She explained that the dual model contains unformed mitochondria.

But Takemura said that these hypotheses are flawed because they can only “explain the appearance of the nucleus” at best. They lack evolutionary logic and cannot explain why the genome is framed and why the protein-making components are excluded. This is also a point that Bell insists: He believes that no other hypothesis can explain why the transcription and translation processes are separated.

The origin of the virus is the most reasonable, and there is the strongest evidence, Fortray said. “I don’t think their theory is necessarily rigorous,” he said of those opponents’ theories. “Viruses play an important role in this theory.”

Waiting for new discoveries

To persuade scientists like Cousins Baum and Lopez Garcia to accept Fortray’s views, more evidence is needed. But 20 years of technological progress may finally make this kind of evidence within reach.

Just in 2020, researchers from Japan announced that after more than ten years of hard work, they finally isolated and cultivated Lokiarchaeota, a kind of archaea believed to have a symbiotic relationship with primitive eukaryotes. . This may allow us to further discover the virus that infects our distant relatives and the process of infection.

David said: “If you find a new type of virus that infects Rocky Archaea, enters the cell and settles there, and makes small holes to facilitate the rapid flow of transcription information into the cytoplasm-this will be more convincing evidence. “It will prove that the nucleus comes from a virus.

Bell noted that researchers recently sequenced a large number of giant viruses in the deep-sea sediments where Rocky Archaea were found. He hopes that someone can test whether any of the viruses can infect archaea, and if so, whether they can build a virus factory similar to the nuclear cytomegalo DNA virus. He said that proving this would “end the game.” Takemura also hopes that this virus does exist. “The discovery of an archaeal virus that can build a membrane and a nucleus-like structure in ancient biological cells will be the strongest evidence that the nucleus originated from a virus,” he said.

Until this extraordinary evidence is available, the theory that the nucleus originated from a virus may still be controversial. But even if it is not recognized by the academic community in the end, every test of the theory will reveal our past evolution bit by bit-and because of this, we are getting closer and closer to the truth of “where did I come from”.

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org