Analysis on “Pfizer’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine only 29% effective”

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Analysis on “Pfizer’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine only 29% effective”

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- What is the difference between Atorvastatin and Rosuvastatin?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Analysis on “Pfizer’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine only 29% effective”.

“The actual effective rate of Pfizer’s vaccine is only 19%-29%?!” Recently, an explosion news about the vaccine has attracted widespread attention.

This question was raised by an epidemiologist Peter Doshi from the School of Pharmacy at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. On January 4th, he published an opinion article as an associate editor of BMJ, which caused an uproar.

Source: BMJ official website screenshot

Source: BMJ official website screenshot

What exactly does this article say? Is the author’s question of Pfizer vaccine reasonable? Dingxiangyuan analyzes and interprets the problems one by one from the following perspectives.

Excluding 3410 “suspected patients”, the actual effective rate is only 29%?

The first point of concern raised by the article is the 3,410 “suspected covid-19” excluded by Pfizer.

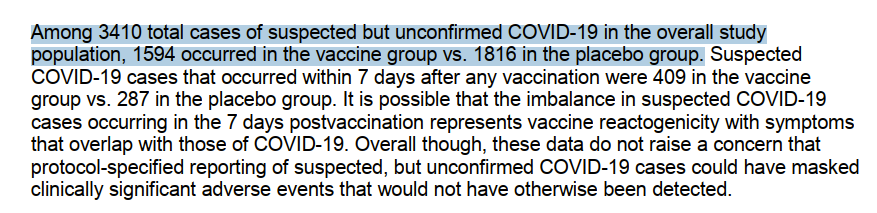

According to the FDA review report, these 3410 “suspected patients” were subjects who had symptoms of COVID-19 but had negative PCR results. Among them, there were 1594 cases in the vaccine group and 1816 cases in the placebo group.

According to the time of onset of symptoms, 696 “suspected patients” appeared within 7 days after vaccination, including 409 in the vaccine group and 287 in the placebo group.

Source: Reference 2

Source: Reference 2

However, in Pfizer’s follow-up reports and papers published in NEJM, only 170 PCR-positive confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported (8 in the vaccine group and 162 in the placebo group), and 3410 “suspected patients” were not mentioned.

The author believes that the number of suspected cases is 20 times more than the number of confirmed cases. The number is very large, and these cases cannot be ignored because of negative PCR test results.

Based on this consideration, the author made two assumptions and calculations.

In the first, he included all 3,410 “suspected patients” into the analysis, and roughly estimated the effectiveness of the vaccine for the symptoms of COVID-19, and the data was 19% = 1 – (8+1594)/(162+1816).

In the second, he excluded 696 suspected cases (409 in the vaccine group and 287 in the placebo group) that had symptoms within 7 days after vaccination, because most of them may be caused by the reactogenicity of the vaccine. This results in a slightly “forgiving” validity: 29% = 1 – (8 + 1594 – 409)/(162 + 1816 – 287).

The author therefore questioned that the true effectiveness of Pfizer’s vaccine may only be 19% to 29%, which is not only far below the officially announced 96%, but also does not meet the WHO threshold requirement for the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine of 50%.

Whether this question is reasonable, we can analyze it from two aspects.

First, it is the definition of “suspected covid-19”.

In the new coronavirus diagnosis and treatment plan issued by the National Health Commission, “suspected patients” mostly refer to cases that have no laboratory or epidemiological evidence but have clinical symptoms and meet the imaging characteristics of new coronavirus pneumonia.

At the beginning of the epidemic, when nucleic acid testing was limited by the specificity of productivity and sensitivity, imaging features were one of the criteria for clinical diagnosis of new coronavirus pneumonia.

The “suspected patients” we talk about most often will eventually become confirmed patients after repeated nucleic acid tests.

In Pfizer’s trial design, subjects will be included in “suspected covid-19” and receive nasopharyngeal swabs whenever they develop symptoms such as fever, search, chills, myalgia, and fatigue. Sub-sampling; if the nucleic acid test is positive, it is considered to be a confirmed patient.

However, Pfizer did not include imaging examinations into the judging criteria. In other words, the “suspected covid-19” mentioned in the article is not the same as the suspected cases we generally understand.

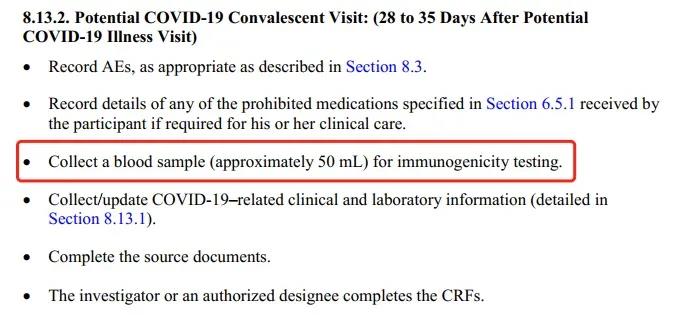

In addition to undergoing nucleic acid testing within three days of the onset of symptoms, these “suspected covid-19” need to be followed up again for serological immunogenicity testing at 28 to 35 days after the onset of symptoms.

Source: Reference 3

Source: Reference 3

Whether there is an infection or not, the antibody test will tell.

A set of rigorous trial designs has basically ruled out the possibility of confirmed cases among “suspected covid-19”.

On the other hand, we can also look at the sensitivity of PCR detection.

In the past year, we have seen asymptomatic infections most frequently, but PCR is positive, but symptomatic patients are rarely seen, but PCR is always negative.

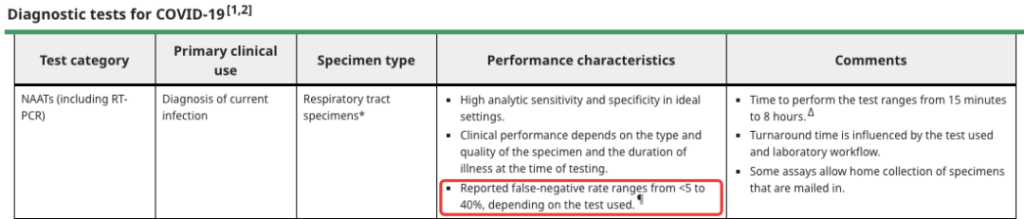

As the gold standard for the diagnosis of new coronavirus pneumonia, the sensitivity of PCR is always above 95%. According to UpToDate data, considering the differences in various detection methods, the false negative rate of RT-PCR is 5% to 40%.

Source: UpToDate screenshot

Source: UpToDate screenshot

According to the author’s first calculation, the PCR false negative rate will reach 95.3%=3410/(170+3410); if according to the author’s second calculation, the PCR false negative rate will also reach 94.1%=(3410-696 )/(3410-696+170).

In other words, the conclusion that “the actual effectiveness of Pfizer vaccine is 19%-29%” needs to be based on the “PCR sensitivity is only 4.7%-5.9%”. Obviously, this data does not conform to scientific facts.

Therefore, we can think that the author’s calculation of the effectiveness of Pfizer’s vaccine is not valid.

“Proposal deviation” excluded 371 cases, the vaccine group was 5 times higher than the control group?

The author’s second concern is that Pfizer excluded 371 subjects due to “important protocol deviation 7 days after the second dose”, including 311 in the vaccine group and 311 in the placebo group. 60 cases.

The author believes that Pfizer did not give a detailed description of the “important program deviation”, and the 371 excluded cases were very unevenly distributed between the vaccine group and the placebo group, and the vaccine group was even 5 times higher.

To understand this problem, we must first give a more general definition of program deviation.

According to the FDA’s previous documents, protocol deviations refer to any changes, dispersion, or deviations from research design or test procedures. The important protocol deviation means that these deviations may significantly affect the completeness, accuracy or reliability of the research data, and may also significantly affect the rights, safety or health of the subjects.

For example, the subjects no longer meet the selection criteria, the researchers have not collected the necessary data… These deviations are all “important program deviations” and may damage the scientific value of the experiment.

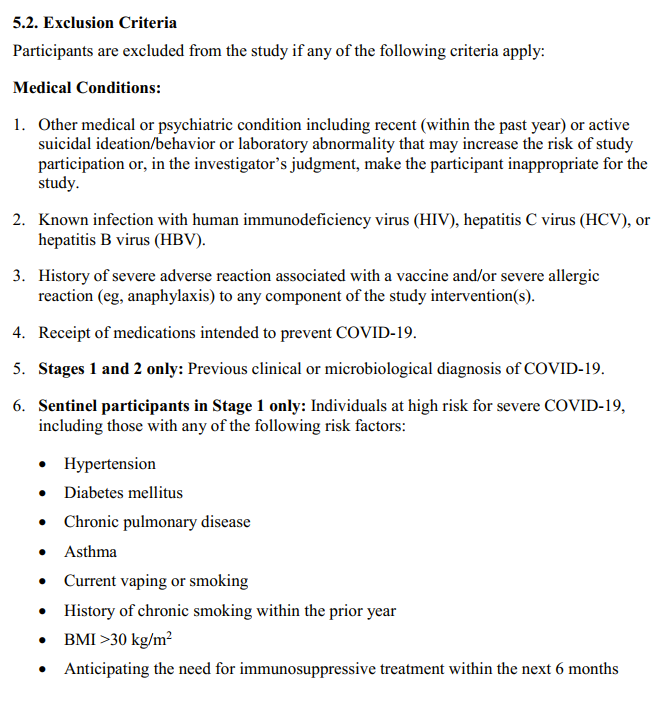

In the Pfizer vaccine trial design, it is also mentioned that during the entire trial process, if subjects no longer fully meet the inclusion criteria, or meet one or more exclusion criteria, they will be immediately excluded.

Therefore, there may not be a correlation between the “important program deviation” and the vaccine, and the uneven distribution of the excluded population among different groups is also likely to be a random event.

The vaccine has obvious immunogenicity. How to ensure double-blind trials?

The author’s third focus is on the use of painkillers and antipyretics.

This author discussed this issue in another article published on November 26, 2020. At that time, he believed that if the vaccine group uses more painkillers and antipyretics than the placebo group, it may cover up the symptoms of the COVID-19 infection, and therefore affect the effectiveness analysis.

Article by Peter Doshi on November 26, 2020

Source: BMJ official website screenshot

However, in the latest article published on January 4, the author re-evaluated the issue. He believes that the more frequent use of painkillers and antipyretics in the vaccine group is mainly due to the immunogenicity of the vaccine, which is the adverse reaction caused by the vaccination itself.

Most of these adverse reactions are short-term, and the use of painkillers and antipyretics is mainly concentrated within 7 days after vaccination, and the two coincide.

Considering that patients diagnosed with COVID-19 often have symptoms for much longer than one week after vaccination, the author believes that the use of painkillers and anti-fever drugs has a very limited impact on the effectiveness of the vaccine.

However, he also put forward another point of view: Subjects/experimenters can judge whether they/subjects received the vaccine or placebo through the significant adverse reactions after vaccination, and this situation will destroy the double-blind trial design.

According to the data of Pfizer’s Phase III study, the adverse reactions after vaccination mainly include discomfort at the injection site (84.1%), fatigue (62.9%), headache (55.1%), myalgia (38.3%), cold war (31.9%), joints Pain (23.6%) and fever (14.2%). In contrast, the placebo group received normal saline injections, and the adverse reactions of the vaccine group were obviously easier to detect.

In theory, in order to maintain the double-blind design of the trial, Pfizer could use a random mRNA sequence of a non-coding antigen and use the same preparation process as the vaccine to create a “placebo” that becomes the control group. However, this assumption is limited to the theoretical level, and there are still many problems with implementation in reality.

In the phase III clinical trial of the chimpanzee adenovirus vector vaccine at the University of Oxford, the tetravalent meningococcal vaccine was selected as a control, which may also be a relatively compromised solution.

Can the vaccine prevent secondary infection?

The author’s fourth focus is on secondary infection.

Source: Reference 6

Source: Reference 6

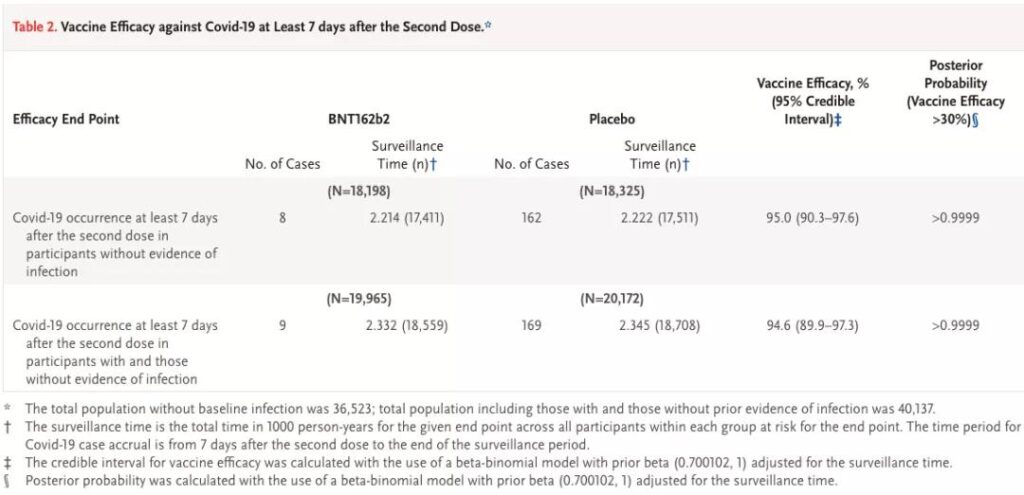

From this table, we can see that seven days after the second vaccination, 170 of the subjects without previous infection history were diagnosed, including 8 in the vaccine group and 162 in the placebo group; and there was a history of previous infection+ A total of 178 cases of subjects with no previous infection history were diagnosed, including 9 cases in the vaccine group (one more case) and 169 cases in the placebo group (up seven cases).

As a subtraction, we know that among subjects with a history of previous infections, 8 patients (1 in the vaccine group and 7 in the placebo group) may have secondary infections.

The author believes that considering that Pfizer reported 1125 cases of previous infections at the baseline, if 8 cases were diagnosed again after the trial, the secondary infection rate would reach 0.71%.

But at present, only 4 to 31 secondary infections have been reported globally, and the figure of 0.71% is obviously high.

Is this question reasonable? In fact, whether “4 to 13 cases” can truly reflect the actual situation of global secondary infections is yet to be determined.

Regarding the topic of secondary infection, the most worthy of our attention should be whether the vaccine can effectively protect the previously infected.

Judging from the data currently published by Pfizer, the effective rates of vaccines covering and excluding secondary infections are 94.6% (95%CI: 89.9%-97.3%) and 95.0% (95%CI: 90.3%-97.6), respectively. %), which means that Pfizer vaccine has shown good effectiveness in both ranges, and the data is not much different.

The CDC mentioned in its review report on Pfizer’s vaccine that “there are no specific safety issues for previously infected people” and “it is recommended that people with or without a history of COVID-19 infection should be vaccinated.” However, due to the small sample size of patients with secondary infections, we currently have no way to obtain the effectiveness of the Pfizer vaccine for previously infected patients.

For vaccine trials, should the raw data be made public?

From 95% to 29%, people’s perception of Pfizer vaccine seems to have gone through a roller coaster. Some voices believe that although the author Peter Doshi’s doubts are not entirely scientifically based, his voice is another challenge to Pfizer.

Others believe that the true effectiveness of Pfizer vaccines may be between 29% and 95%. However, discussing such a scope is of limited significance for our understanding and evaluation of a vaccine.

Without the disclosure of detailed information, we may never get an exact answer. But from the current point of view, the results that Pfizer has published and reviewed by the FDA are obviously more scientific and more convincing.

At the end of the article, the author believes that only vaccine research and development companies can disclose the original test data to solve these problems and doubts.

But in fact, the original data of clinical trials may themselves belong to commercial company secrets and contain a large number of subjects’ privacy that cannot be disclosed. Are commercial companies obligated to share or disclose these contents to a wider group of people on the premise that they operate legally and comply with the review of regulatory agencies? This issue is still open for discussion.

In the COVID-19 epidemic, vaccines have become the focus of people’s concern and discussion. In this era, the issue of data transparency has therefore become more sensitive.

Commercial companies have the right to choose to selectively disclose some raw data at any point in time for their own commercial considerations, provided that they do not violate any regulations. But with the popularization of vaccine science knowledge, commercial companies should also try to make data more transparent.

After all, only by increasing the credibility and acceptability of products can we seize the high ground and advance mass vaccination more quickly.

Analysis on “Pfizer’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine only 29% effective”

Analysis on “Pfizer’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine only 29% effective”

Reference materials:

[1]Peter Doshi: Pfizer and Moderna’s “95% effective” vaccines—we need more details and the raw data

[2]Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting.December 10, 2020.FDA Briefing Document.Sponsor:Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine

[3]A PHASE 1/2/3, PLACEBO-CONTROLLED, RANDOMIZED, OBSERVER-BLIND, DOSE-FINDING STUDY TO EVALUATE THE SAFETY, TOLERABILITY, IMMUNOGENICITY, AND EFFICACY OF SARS-COV-2 RNA VACCINE CANDIDATES AGAINST COVID-19 IN HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS

[4]Guidance for Industry E3 Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports Questions and Answers (R1).FDA

[5]Peter Doshi: Pfizer and Moderna’s “95% effective” vaccines—let’s be cautious and first see the full data

[6]Polack F P, Thomas S J, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine[J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2020.

[7]Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States.CDC

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org