Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

Where did the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 that is currently ravaging the world come from? At present, scientists have put forward three hypotheses: genetic mutation , chronic infection , and introduction from other animals .

At present, the COVID-19 Omicron variant has been spreading rapidly around the world, and it has been less than two months since its first discovery. As scientists track the virus closely, they remain baffled by a key question:

Where did Omicron come from?

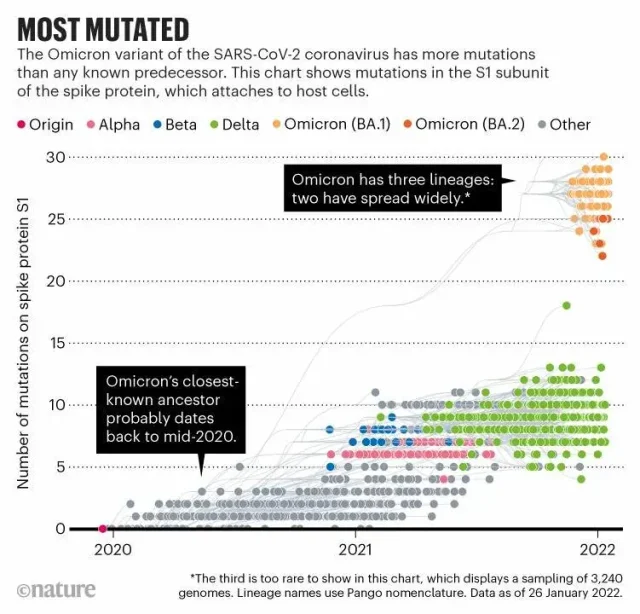

Omicron is so different from earlier variants , such as Alpha and Delta , that evolutionary virologists estimate that its closest known genetic ancestor may date back more than a year, sometime after mid-2020.

” It came out of nowhere,” said Darren Martin, a computational biologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa .

The question of Omicron’s origins isn’t just academically important. Figuring out under what conditions this highly contagious variant emerges may help scientists understand new the risk of variants appearing and recommending measures to minimize them.

The World Health Organization’s recently established Scientific Advisory Group on the Origin of Novel Pathogens (SAGO) met in January to discuss the origin of Omicron. SAGO president Marietjie Venter, a medical virologist at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, said the group expects to publish a report in early February.

Ahead of the report, scientists were working on three possible theories. A series of mutations that ultimately lead to Omicron may be missed. Alternatively, the mutation may evolve in a person as part of a long-term infection. Alternatively, it may be present in other animal hosts, such as mice or rats.

Whichever view researchers tend to lean toward, it’s based on intuition, not any principled argument, says computational biologist Richard Neher of the University of Basel in Switzerland.

Hypothesis 1: “Hell-like” crazy genetic mutation

Researchers agree that Omicron is a relatively recent phenomenon.

It was first detected in South Africa and Botswana in early November 2021; since then, earlier individual samples have been found in England on November 1-3 and in South Africa, Nigeria and the United States on November 2. After analysis, it was found that it appeared earlier than the end of September or the beginning of October last year.

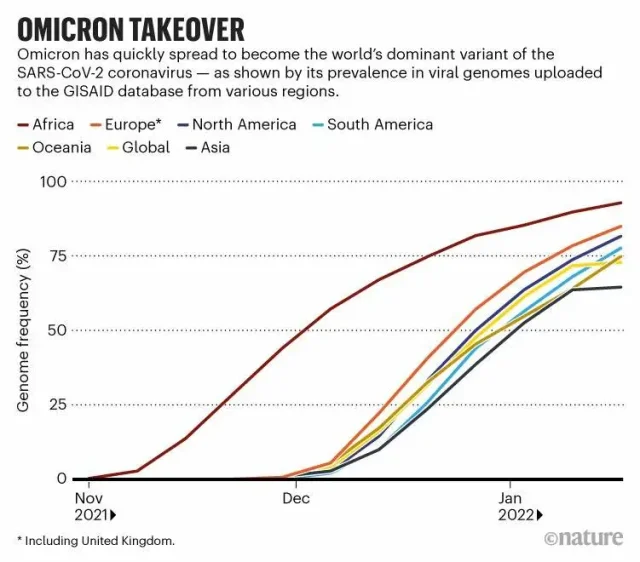

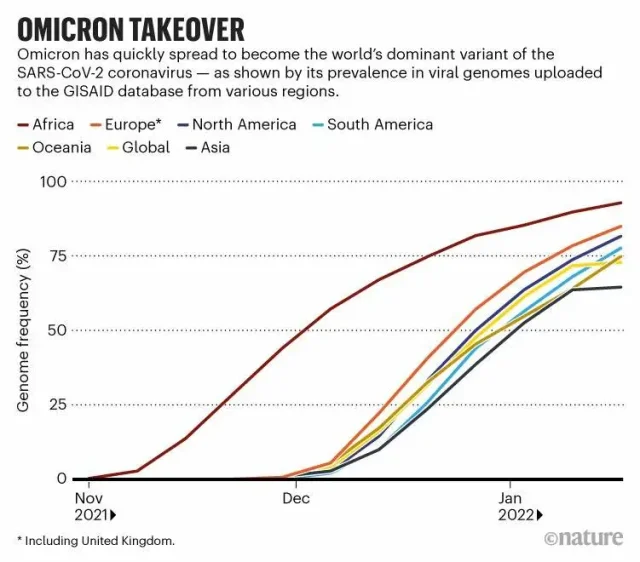

Line graph of the prevalence of Omicron in genomes uploaded to the database from various regions. Source: GISAID

But since Johannesburg is home to the continent’s largest airport, Omicron could actually have originated anywhere in the world — only to be found in South Africa, said Tulio de Oliveira, a bioinformatician who led the South African tracker including Efforts to mutate viruses, including Omicron.

A technician in a protective suit works in a laboratory that studies variants of the omicron SARS-CoV-2.

Upasana Ramphal, a doctoral student in Tulio de Oliveira’s lab at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, and his team have been working to track Omicron and other variants in southern Africa. Photo credit: Joao Silva/NYT/Redux/eyevine

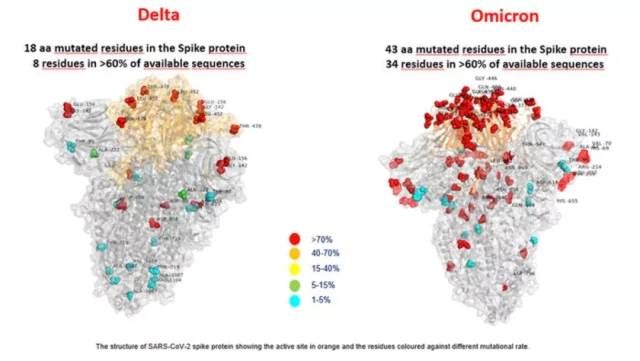

The distinguishing feature of Omicron is that there are significantly more mutation sites. Compared to the original SARS-CoV-2 virus, this variant has more than 50 mutations, about 30 of which result in amino acid changes in the spike protein, which the virus uses to attach and fuse with cells. In previous virus variants, there were no more than ten such mutations.

“It’s a hell of a mutation,” Neher said.

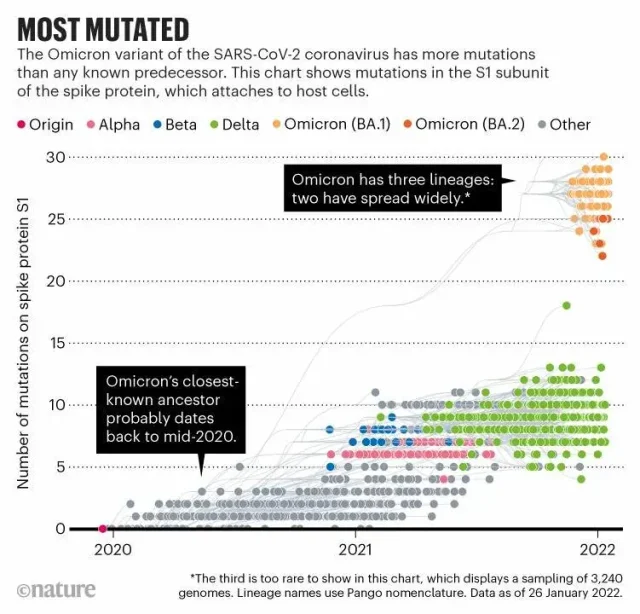

The graph shows the number of mutations in the spike protein S1 of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus over time. Source: Nextstrain

Omicron has more control over ACE2 than previously discovered variants, and is better able to avoid virus-blocking “neutralizing” antibodies produced by people who have been vaccinated or infected with earlier variants.

Also, other changes in the spike protein appear to alter the way Omicron enters the cell: it appears to be less adept at fusing directly with the cell membrane, preferring instead to enter the cell after being engulfed by the endosome.

Another curious feature of Omicron is that, from a genomic perspective, it consists of three distinct sublineages (called BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3) that all appear to have emerged around the same time. That means Omicron has time to diversify mutations before scientists notice.

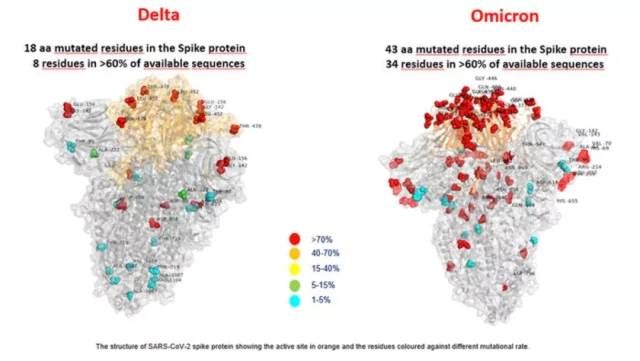

Comparison of spike protein mutations between delta strain and Omicron strain

Comparison of spike protein mutations between delta strain and Omicron strain

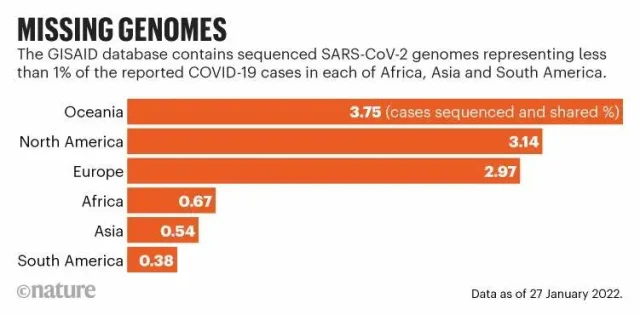

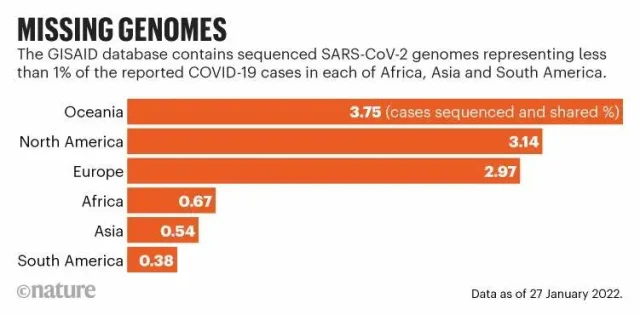

Although researchers have submitted nearly 7.5 million SARS-CoV-2 sequences to the GISAID genome database, hundreds of millions of viral genomes from COVID-19 patients worldwide have yet to be sequenced.

Currently, South Africa has sequenced less than 1% of its known COVID-19 cases, while many neighboring countries, from Tanzania to Zimbabwe and Mozambique, have submitted fewer than 1,000 sequences to GISAID.

Percentage of genomes sequenced for percent of reported COVID-19 cases by region. Source: GISAID

Researchers need to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genomes in these countries to better understand the possibility of unobserved evolution, Martin said. It is possible, he said, that three sub-lineages of Omicron arrived in South Africa separately from regions with limited sequencing capacity.

“This is not the 19th century, where you need six months to sail from one point to another by sailboat,” said computational evolutionary biologist Sergey Pound of Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hypothesis 2: Chronic infection in humans

The second theory is that chronic infection in humans acts as an “incubator” for Omicron.

In chronically infected patients, the virus can multiply for weeks or months and develop different types of mutations to evade the body’s immune system. Chronic infection gives the virus a chance to play a cat-and-mouse game with the immune system, Pond said, which he thinks is a plausible hypothesis for Omicron’s emergence.

Such chronic infections have been observed in people with compromised immune systems. For example, a December 2020 case report described persistent infection in a 45-year-old man. Over nearly five months in the host, SARS-CoV-2 accumulated nearly a dozen amino acid changes in its spike protein.

Some researchers believe that it is this long-term existence in the host that gives the virus more suitable evolutionary conditions and may be one of the important factors for Omicron.

“Viruses have to change to survive,” says Ben Murrell, an interdisciplinary virologist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. Omicron’s many mutations are concentrated in the receptor-binding domain, which is an easy target for antibodies that must alter itself to survive long-term infections.

But none of the viruses in chronically infected individuals studied so far have the scale of mutation observed in Omicron. Achieving this, Rasmussen said, would require prolonged periods of high viral replication rates, which can be very uncomfortable for patients.

Further complicating the situation, Omicron’s properties may arise from a combination of mutations. For example, two mutations found in Omicron — N501Y and Q498R — increased one variant’s ability to bind to the ACE2 protein by nearly 20-fold, according to cell studies.

Preliminary studies by Martin et al show that a dozen rare mutations in Omicron form three separate clusters that work together to compensate for each other’s negative effects.

If this is the case, it means that the virus must replicate sufficiently in the human body to explore the effects of a combination of mutations — which would take longer than sampling the possible mutation space one by one.

It is also possible that the production of Omicron involved multiple chronically infected patients, or that the pre-Omicron virus came from chronically infected patients and then survived in the general population for a period of time before being discovered. “Right now, there are a lot of unanswered questions,” Rasmussen said.

Proving this theory is nearly impossible because researchers would need to be very lucky to find a specific individual or group that might have triggered the emergence of Omicron. Still, Neher said, a more comprehensive study of how SARS-CoV-2 changes in chronic infection will help determine the likely scope of Omicron.

Hypothesis 3: The culprit is the mouse?

Another possibility is that Omicron may not have come from humans at all.

SARS-CoV-2 is a promiscuous virus: it has now spread to wild leopards, hyenas and hippos in zoos, and pet ferrets and hamsters. Omicron may be able to spread among a wider range of animals. The study found that, unlike earlier virus variants, Omicron’s spike protein can bind to the ACE2 protein in turkey, chicken and mice.

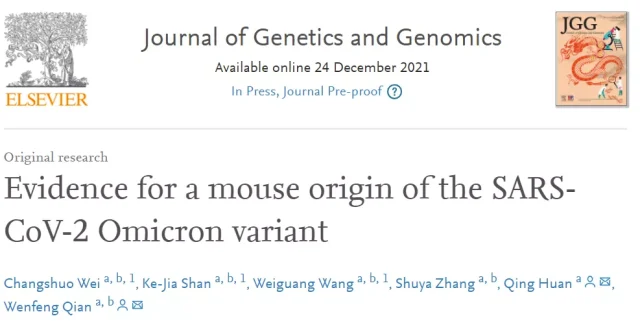

On December 24, 2021, the team of researcher Qian Wenfeng from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences published a research paper titled: Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant online in the Journal of Genetics and Genomics . The study revealed that the transmission route of Omicron is most likely from humans to house mice and back to humans after long-term evolution.

Looking at it this way, it is possible that SARS-CoV-2 acquired a mutation that allowed it to spread from humans to mice—jumping from patient to mouse, then spreading among animal populations and evolving into Omicron.

Infected mice may later come into contact with humans, triggering the emergence of Omicron. The three subclades of Omicron are very different, and according to this theory, each subclade represents a separate jump spread from animals to humans.

Some animals have a much longer infection period than humans, giving SARS-CoV-2 a wider space for multiple mutations and creating a large number of unknown “virus ghosts”. This “back-propagation” theory has some credibility. Changes that make the virus better spread among animal hosts don’t necessarily affect its ability to infect humans, he said.

This hypothesis could also explain why some mutations in Omicron were previously rare in humans.

Omicron origin may never be found

As mentioned above, at present, these three theories about the origin of Omicron are only hypotheses of scientists.

There are many opportunities for the virus to spread from person to person. Even though some Omicron mutations have been found in rodents, that doesn’t mean they didn’t happen in humans, it’s just that we didn’t.

Now that Omicron has become popular globally, figuring out its evolutionary route in humans could provide more clues about its origins.

The researchers said that the answer to “where did Omicron come from” may be one of these three situations, or it may be the result of a combination of factors. It is still not completely scientifically explained. As for predicting the next variant will be What it looks like is a further matter.

Some scientists say that we may never find the source of Omicron.

“Omicron’s example illustrates the need for constant humility in our ability to understand the evolutionary process of viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.”

References :

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00215-2

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03619-8

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2021.12.003

https://newsaf.cgtn.com/news/2021-11-28/Italy-announces-first-detected-case-of-omicron-COVID-19-variant-15xI1h5Zk2I/index.html

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/south-african-scientists-brace-for-wave-propelled-by-omicron

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

Where did the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 that is currently ravaging the world come from? At present, scientists have put forward three hypotheses: genetic mutation , chronic infection , and introduction from other animals .

At present, the COVID-19 Omicron variant has been spreading rapidly around the world, and it has been less than two months since its first discovery. As scientists track the virus closely, they remain baffled by a key question:

Where did Omicron come from?

Omicron is so different from earlier variants , such as Alpha and Delta , that evolutionary virologists estimate that its closest known genetic ancestor may date back more than a year, sometime after mid-2020.

” It came out of nowhere,” said Darren Martin, a computational biologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa .

The question of Omicron’s origins isn’t just academically important. Figuring out under what conditions this highly contagious variant emerges may help scientists understand new the risk of variants appearing and recommending measures to minimize them.

The World Health Organization’s recently established Scientific Advisory Group on the Origin of Novel Pathogens (SAGO) met in January to discuss the origin of Omicron. SAGO president Marietjie Venter, a medical virologist at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, said the group expects to publish a report in early February.

Ahead of the report, scientists were working on three possible theories. A series of mutations that ultimately lead to Omicron may be missed. Alternatively, the mutation may evolve in a person as part of a long-term infection. Alternatively, it may be present in other animal hosts, such as mice or rats.

Whichever view researchers tend to lean toward, it’s based on intuition, not any principled argument, says computational biologist Richard Neher of the University of Basel in Switzerland.

Hypothesis 1: “Hell-like” crazy genetic mutation

Researchers agree that Omicron is a relatively recent phenomenon.

It was first detected in South Africa and Botswana in early November 2021; since then, earlier individual samples have been found in England on November 1-3 and in South Africa, Nigeria and the United States on November 2. After analysis, it was found that it appeared earlier than the end of September or the beginning of October last year.

Line graph of the prevalence of Omicron in genomes uploaded to the database from various regions. Source: GISAID

But since Johannesburg is home to the continent’s largest airport, Omicron could actually have originated anywhere in the world — only to be found in South Africa, said Tulio de Oliveira, a bioinformatician who led the South African tracker including Efforts to mutate viruses, including Omicron.

A technician in a protective suit works in a laboratory that studies variants of the omicron SARS-CoV-2.

Upasana Ramphal, a doctoral student in Tulio de Oliveira’s lab at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, and his team have been working to track Omicron and other variants in southern Africa. Photo credit: Joao Silva/NYT/Redux/eyevine

The distinguishing feature of Omicron is that there are significantly more mutation sites. Compared to the original SARS-CoV-2 virus, this variant has more than 50 mutations, about 30 of which result in amino acid changes in the spike protein, which the virus uses to attach and fuse with cells. In previous virus variants, there were no more than ten such mutations.

“It’s a hell of a mutation,” Neher said.

The graph shows the number of mutations in the spike protein S1 of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus over time. Source: Nextstrain

Omicron has more control over ACE2 than previously discovered variants, and is better able to avoid virus-blocking “neutralizing” antibodies produced by people who have been vaccinated or infected with earlier variants.

Also, other changes in the spike protein appear to alter the way Omicron enters the cell: it appears to be less adept at fusing directly with the cell membrane, preferring instead to enter the cell after being engulfed by the endosome.

Another curious feature of Omicron is that, from a genomic perspective, it consists of three distinct sublineages (called BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3) that all appear to have emerged around the same time. That means Omicron has time to diversify mutations before scientists notice.

Comparison of spike protein mutations between delta strain and Omicron strain

Comparison of spike protein mutations between delta strain and Omicron strain

Although researchers have submitted nearly 7.5 million SARS-CoV-2 sequences to the GISAID genome database, hundreds of millions of viral genomes from COVID-19 patients worldwide have yet to be sequenced.

Currently, South Africa has sequenced less than 1% of its known COVID-19 cases, while many neighboring countries, from Tanzania to Zimbabwe and Mozambique, have submitted fewer than 1,000 sequences to GISAID.

Percentage of genomes sequenced for percent of reported COVID-19 cases by region. Source: GISAID

Researchers need to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genomes in these countries to better understand the possibility of unobserved evolution, Martin said. It is possible, he said, that three sub-lineages of Omicron arrived in South Africa separately from regions with limited sequencing capacity.

“This is not the 19th century, where you need six months to sail from one point to another by sailboat,” said computational evolutionary biologist Sergey Pound of Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hypothesis 2: Chronic infection in humans

The second theory is that chronic infection in humans acts as an “incubator” for Omicron.

In chronically infected patients, the virus can multiply for weeks or months and develop different types of mutations to evade the body’s immune system. Chronic infection gives the virus a chance to play a cat-and-mouse game with the immune system, Pond said, which he thinks is a plausible hypothesis for Omicron’s emergence.

Such chronic infections have been observed in people with compromised immune systems. For example, a December 2020 case report described persistent infection in a 45-year-old man. Over nearly five months in the host, SARS-CoV-2 accumulated nearly a dozen amino acid changes in its spike protein.

Some researchers believe that it is this long-term existence in the host that gives the virus more suitable evolutionary conditions and may be one of the important factors for Omicron.

“Viruses have to change to survive,” says Ben Murrell, an interdisciplinary virologist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. Omicron’s many mutations are concentrated in the receptor-binding domain, which is an easy target for antibodies that must alter itself to survive long-term infections.

But none of the viruses in chronically infected individuals studied so far have the scale of mutation observed in Omicron. Achieving this, Rasmussen said, would require prolonged periods of high viral replication rates, which can be very uncomfortable for patients.

Further complicating the situation, Omicron’s properties may arise from a combination of mutations. For example, two mutations found in Omicron — N501Y and Q498R — increased one variant’s ability to bind to the ACE2 protein by nearly 20-fold, according to cell studies.

Preliminary studies by Martin et al show that a dozen rare mutations in Omicron form three separate clusters that work together to compensate for each other’s negative effects.

If this is the case, it means that the virus must replicate sufficiently in the human body to explore the effects of a combination of mutations — which would take longer than sampling the possible mutation space one by one.

It is also possible that the production of Omicron involved multiple chronically infected patients, or that the pre-Omicron virus came from chronically infected patients and then survived in the general population for a period of time before being discovered. “Right now, there are a lot of unanswered questions,” Rasmussen said.

Proving this theory is nearly impossible because researchers would need to be very lucky to find a specific individual or group that might have triggered the emergence of Omicron. Still, Neher said, a more comprehensive study of how SARS-CoV-2 changes in chronic infection will help determine the likely scope of Omicron.

Hypothesis 3: The culprit is the mouse?

Another possibility is that Omicron may not have come from humans at all.

SARS-CoV-2 is a promiscuous virus: it has now spread to wild leopards, hyenas and hippos in zoos, and pet ferrets and hamsters. Omicron may be able to spread among a wider range of animals. The study found that, unlike earlier virus variants, Omicron’s spike protein can bind to the ACE2 protein in turkey, chicken and mice.

On December 24, 2021, the team of researcher Qian Wenfeng from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences published a research paper titled: Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant online in the Journal of Genetics and Genomics . The study revealed that the transmission route of Omicron is most likely from humans to house mice and back to humans after long-term evolution.

Looking at it this way, it is possible that SARS-CoV-2 acquired a mutation that allowed it to spread from humans to mice—jumping from patient to mouse, then spreading among animal populations and evolving into Omicron.

Infected mice may later come into contact with humans, triggering the emergence of Omicron. The three subclades of Omicron are very different, and according to this theory, each subclade represents a separate jump spread from animals to humans.

Some animals have a much longer infection period than humans, giving SARS-CoV-2 a wider space for multiple mutations and creating a large number of unknown “virus ghosts”. This “back-propagation” theory has some credibility. Changes that make the virus better spread among animal hosts don’t necessarily affect its ability to infect humans, he said.

This hypothesis could also explain why some mutations in Omicron were previously rare in humans.

Omicron origin may never be found

As mentioned above, at present, these three theories about the origin of Omicron are only hypotheses of scientists.

There are many opportunities for the virus to spread from person to person. Even though some Omicron mutations have been found in rodents, that doesn’t mean they didn’t happen in humans, it’s just that we didn’t.

Now that Omicron has become popular globally, figuring out its evolutionary route in humans could provide more clues about its origins.

The researchers said that the answer to “where did Omicron come from” may be one of these three situations, or it may be the result of a combination of factors. It is still not completely scientifically explained. As for predicting the next variant will be What it looks like is a further matter.

Some scientists say that we may never find the source of Omicron.

“Omicron’s example illustrates the need for constant humility in our ability to understand the evolutionary process of viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.”

References :

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00215-2

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03619-8

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2021.12.003

https://newsaf.cgtn.com/news/2021-11-28/Italy-announces-first-detected-case-of-omicron-COVID-19-variant-15xI1h5Zk2I/index.html

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/south-african-scientists-brace-for-wave-propelled-by-omicron

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about?

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about? Nature: How did…

co

Nature: How did the “Omicron” that ravaged the world come about? Nature: How did…

co