Necessary to change Lorlatinib after patients with NSCLC has progressed?

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Necessary to change Lorlatinib after patients with NSCLC has progressed?

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Necessary to change Lorlatinib after patients with NSCLC has progressed?

JTO: Subversion of cognition! ALK targeted drug treatment of lung cancer progresses, don’t rush to change the drug

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer, accounting for about 85% of lung cancers [1], of which the detection rate of “golden mutation” ALK mutation is about 3% to 8% [2].

In response to this golden mutation, multiple generations of ALK inhibitors have been approved for marketing, and the therapeutic effect has been continuously improved [3, 4].

The third-generation ALK inhibitor Lorlatinib (Lorlatinib, formerly known as Lorlatinib) has the advantages of strong efficacy and high blood-brain barrier permeability, and has long-lasting effects on lung tumors and brain metastases in patients.

At present, Lorlatinib has been approved abroad for the first-line treatment of patients with ALK mutations, as well as the second-line treatment of patients with disease progression after receiving at least one other ALK inhibitor treatment, and will soon be launched in China.

Lorlatinib, as a follow-up treatment after resistance to first- and second-generation ALK inhibitors, can cover multiple gene mutation sites associated with resistance to other ALK inhibitors.

However, in patients with NSCLC whose disease has progressed after Lorlatinib treatment, can Lorlatinib continue to be used? Is there any clinical benefit to continuation of the drug?

With these questions in mind, a team led by Professor Sai-Hong Ignatius Ou of the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine recently published an important research result in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology [5]. They retrospectively analyzed a phase II clinical trial (NCT01970865) and found that continued Lorlatinib maintenance therapy (LBPD) after disease progression could still benefit patients with ALK mutation-positive NSCLC .

This phase II clinical trial[6] included a total of 124 NSCLC patients who progressed after treatment with an ALK inhibitor.

The researchers evaluated tumors (including brain metastases) every 6 weeks, and only 102 patients were finally treated with loratibide.

Patients with NSCLC who responded well (CR or PR or SD) to initial therapy were included in the analysis.

The researchers divided these patients into two groups, patients in group A (n=28) who had previously used only a first-generation ALK inhibitor (crizotinib), and patients in group B (n=74) who had previously used at least one first-generation ALK inhibitor (crizotinib). Second-generation ALK inhibitors.

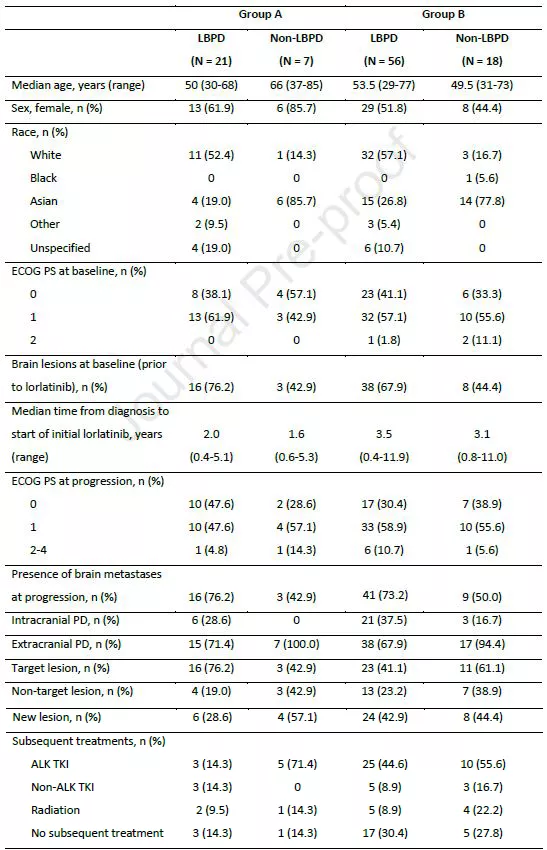

The patients in the two groups were further divided into the LBPD group and the non-LBPD group according to whether LBPD was performed, that is, continued Lorlatinib maintenance therapy for more than 3 weeks after disease progression.

The investigators assessed the clinical characteristics of the two groups of patients at baseline and progression, the efficacy of Lorlatinib, the mode of progression, the duration of treatment (DoT) from first dose to progression, and the overall survival (OS) from first dose to progression. ) for analysis.

Clinical characteristics of patients at baseline and progression

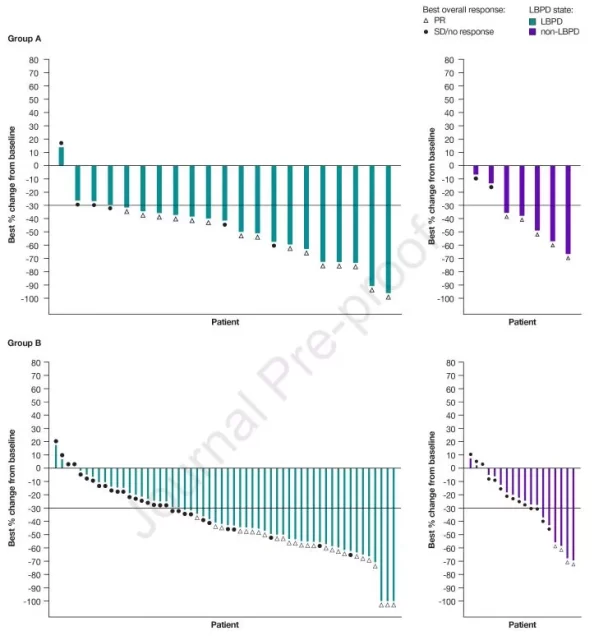

First, the researchers compared the response of the two groups of patients to initial Lorlatinib treatment.

In arm A, there was no difference in initial treatment response to Lorlatinib between LBPD patients and non-LBPD patients, with ORRs of 71.4% for both.

In arm B, LBPD patients had a higher response to initial treatment with Lorlatinib than non-LBPD patients (46.4% vs. 22.2%).

Patient response to initial Lorlatinib therapy

In arm A, intracranial ORR was higher in non-LBPD patients than in LBPD patients (66.7% vs. 37.5%).

In group B, non-LBPD patients had lower intracranial ORR than LBPD patients (25.0% vs. 39.5%).

Median time from baseline to disease progression was similar between LBPD and non-LBPD patients in both groups.

Next, the researchers compared the pattern of disease progression after Lorlatinib treatment and found that both groups of LBPD patients had less extracranial progression than non-LBPD patients.

In arm A, LBPD patients had more primary tumor progression but fewer new metastases than non-LBPD patients; in arm B, both LBPD patients and non-LBPD patients experienced extensive progression, including primary tumor progression and new metastases Metastases appear.

About a quarter of non-LBPD patients did not receive any follow-up treatment after disease progression. Among the patients who underwent subsequent therapy, a large proportion of patients received other ALK inhibitors (71.4% in group A and 55.6% in group B).

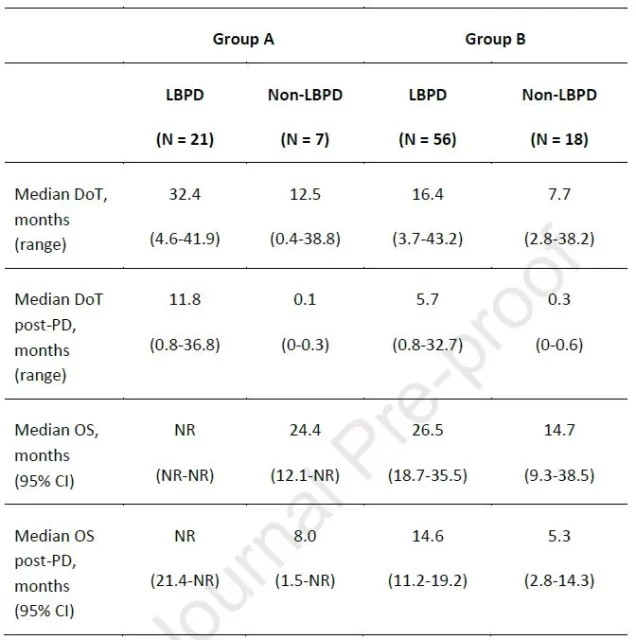

Then came the most important part of the study, where the researchers analyzed the impact of LBPD on patient outcomes.

They found that the median DoT of patients with LBPD in groups A and B before and after disease progression was 32.4 months and 16.4 months, respectively, while the median DoT of non-LBPD patients was significantly lower, 12.5 months and 7.7 months, respectively; A The median DoT of LBPD patients in group B and group B after disease progression was 11.8 months and 5.7 months, respectively .

Comparison of patient outcomes

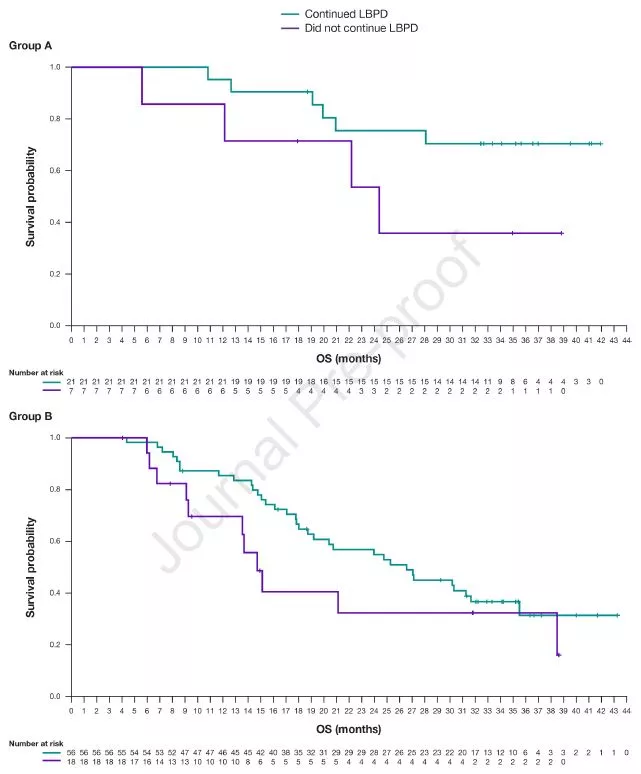

As of the follow-up cut-off date (May 14, 2019), the median OS for LBPD patients in arm A had not been reached (NR), and the median OS for non-LBPD patients was 24.4 months (95% CI: 12.1-NR); in arm B , the median OS of LBPD patients was significantly higher than that of non-LBPD patients, which were 26.5 months (95% CI: 18.7-35.5) and 14.7 months (95% CI: 9.3-38.5), respectively .

OS in two groups of LBPD patients

Similarly, in arm A, median OS after disease progression was NR (95% CI: 21.4 months-NR) and 8.0 months (95% CI: 1.5-NR) in patients with LBPD and non-LBPD patients, respectively; The median OS after disease progression was 14.6 months (95% CI: 11.2-19.2) and 5.3 months (95% CI: 2.8-14.3) in patients with LBPD and non-LBPD patients, respectively.

The above results suggest that LBPD significantly prolongs the survival of patients , so is the quality of life also improved?

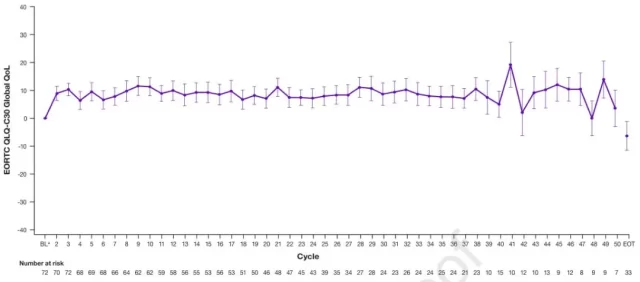

The researchers used the European Organization for Cancer Research and Treatment Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) scoring questionnaire to analyze changes in patients’ quality of life during treatment.

The results showed that patients’ quality of life continued to improve over time, even during disease progression.

It can be seen that LBPD can not only prolong the survival period, but also ensure the quality of life.

Changes in EORTC QLQ-C30 global quality of life scores in LBPD patients

Previous studies have shown that with the increase in the number of lines of second-generation ALK inhibitors, the PFS of Lorlatinib treatment will also decrease [7].

Similar conclusions were reached in this study—after progression on initial Lorlatinib therapy, patients in group A who had only used first-generation ALK-TKI crizotinib had a higher median DoT than those in group B who had used second-generation TKIs.

Therefore, if multiple rounds of ALK inhibitors are used sequentially, it may accelerate the generation of ALK resistance gene mutations and reduce the efficacy of Lorlatinib.

Overall, for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC who responded well to initial Lorlatinib therapy, continuation of Lorlatinib therapy after disease progression could improve patient outcomes.

However, this is only a retrospective study, and its results may be affected by selection bias.

It is hoped that there will be more clinical data to prove the efficacy and safety of this method of use of Lorlatinib.

References:

[1] Friedlaender, A., A. Addeo, A. Russo, et al., Targeted Therapies in Early Stage NSCLC: Hype or Hope? Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(17).

[2] Devarakonda, S., D. Morgensztern, R. Govindan, Genomic alterations in lung adenocarcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16(7): e342-351.

[3] Golding, B., A. Luu, R. Jones, et al., The function and therapeutic targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Mol Cancer. 2018, 17( 1): 52.

[4] Bauer, TM, AT Shaw, ML Johnson, et al., Brain Penetration of Lorlatinib: Cumulative Incidences of CNS and Non-CNS Progression with Lorlatinib in Patients with Previously Treated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Target Oncol. 2020, 15(1): 55-65.

[5] Ou, SI, BJ Solomon, AT Shaw, et al., Continuation of Lorlatinib in ALK-positive NSCLC Beyond Progressive Disease. J Thorac Oncol. 2022.

[6] Solomon, BJ, B. Besse, TM Bauer, et al., Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19(12) : 1654-1667.

[7] Zhu, VW, YT Lin, DW Kim, et al., An International Real-World Analysis of the Efficacy and Safety of Lorlatinib Through Early or Expanded Access Programs in Patients With Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Refractory ALK-Positive or ROS1- Positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2020, 15(9): 1484-1496.

Necessary to change Lorlatinib after patients with NSCLC has progressed?

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.