Science Hot Discussion: Why are so few women Nobel Prize winners?

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

Science Hot Discussion: Why are so few women Nobel Prize winners?

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Science Hot Discussion: Why are so few women Nobel Prize winners?

Only 17 women in 115 years! Why do men often sweep the Nobel Prize and so few women winners?

This year’s Nobel Prizes are also awarded to men. On October 12th, researchers discussed in “Science” why men have often swept the Nobel Prize in recent years, while women are rarely nominated.

Since the Nobel Prize was first awarded in 1901, there have only been 17 women winners in 115 years. In recent years, calls for solving the gender imbalance between Nobel Prize winners and the scarcity of more women and scientists from around the world have reached a feverish level.

Nobel Prize Committee members shared a summary of the data with “Science”: it shows that in recent years, changes in this process have almost doubled the proportion of nominated women, but still hope that more women will be nominated.

In addition, there is room for improvement in the composition of the selection committee itself, and the proportion of women is also small. Of course, there is no gender “discrimination” when the committee discusses the Nobel Prize.

We also need to solve this problem ourselves and work hard to solve the problem of underrepresentation of women in leading academic positions.

Since the Nobel Prize was first awarded in 1901, a total of 581 people have won the Nobel Prize in Natural Science, of which only 17 are female winners. The number of female Nobel Prize winners in Natural Science only accounts for 2.93% of the total number of winners.

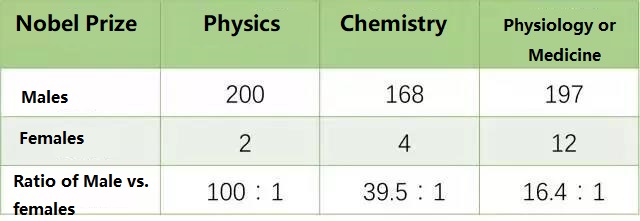

If the statistics are based on the award-winning disciplines, the gender imbalance phenomenon of the Nobel Prize in Natural Science will be more vivid through the following table:

Distribution of male and female Nobel Prize winners in natural sciences from 1901 to 2016

The seven Nobel Prize winners in the 2016 Science Prize were all men, and in 2015 there was only one woman Tu Youyou. On October 5, 2015, Chinese female pharmacist Tu Youyou won the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The first Nobel prize winner was Marie Curie, who awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903.

The list of all-male winners of the Nobel Prize in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine this year is also a bit disappointing, but it does not completely shock the scientific community. This fits most of the 121-year history of the Nobel Foundation: in the past 18 years, only one woman has been a science prize winner.

Now, members of the two award committees have shared internal figures with Science magazine. These figures highlight one reason for this discrepancy: Although the number of women nominations for science awards has doubled in recent years, they are still very small. On October 12, the researchers published an article titled “One reason men often sweep the Nobels: few women nominees” in “Science”.

doi: 10.1126/science.acx9351

doi: 10.1126/science.acx9351

Even after the recent increase in nominations, only 13% of physiology or medicine nominees are women, and only 7% to 8% of chemistry nominees are women. Jo Handelsman, a molecular biologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who has been studying gender bias in the scientific community, said: “This has always been a question of many high-level and prestigious awards: If (women) are not in the selection, you You cannot choose them.”

This year’s knockout competition was followed by an eye-catching women’s year: three of the eight science prize winners in 2020 were women, and one—the Nobel Prize in Chemistry—was awarded to a pair of women, no men. Liselotte Jauffred, a physicist at the University of Copenhagen, has been studying the odds of women winning the Nobel Prize. He said: “I think the situation last year was very optimistic. Maybe it has really changed, but now we are back to normal.”

In recent years, calls for solving the gender imbalance between Nobel Prize winners and the scarcity of people of color and scientists outside North America and Europe have reached a feverish level.

In 2018, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics and Nobel Prize in Chemistry, announced changes to the nomination process to encourage greater diversity.

The selection committee expanded the list of people invited to submit nominations to include more women and scientists from all over the world. They also adjusted the wording in the invitation letter to clearly mention underrepresented groups and asked scientists to nominate at least three findings, not just one. The Karolinska Institute, which awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, also made some similar changes.

The nomination committee usually keeps the data of nominators confidential, citing the Nobel Foundation Statutes: Nominations must be kept confidential for 50 years. But committee members shared a summary of the data with “Science” magazine.

The total number of nominations for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has jumped from about 350 in 2015 to 874 this year. In these years, the proportion of female nominees has more than doubled, from 5% in 2015 to 13% this year.

The Chemistry Committee has seen similar growth: since 2018, the proportion of female nominees has doubled, from 7% to 8%. A representative of the Physics Committee declined to disclose the exact number, but wrote in an email: “In the past few years, the number of women nominated has increased significantly.”

Nonetheless, “if these numbers don’t lead to more and more women receiving the award, they are of little significance,” said Lokman Meho, an information scientist at Georgetown University in Qatar. A study published in “Quantitative Science Studies” in August showed that the gender difference of Nobel Prize winners is greater than that of other famous science, engineering and mathematics prize winners.

The members of the selection committee who have the right to screen nominations stated that they are not satisfied with the progress of the nomination. Pernilla Wittung Stafshede, a biophysical chemist at Chalmers University of Technology, one of the two female members of the eight-person chemistry committee, said: “The proportion of women in nominees is very low.

The percentage of women.” “We hope that more women will be nominated.” Eva Olsson, an experimental physicist at Chalmers and a member of the Physics Selection Committee, agreed with this view.

Wittung-Stafshede added that in addition to finding ways to increase the number of women nominated, the committee may also want to broaden their horizons and see what findings are worthy of the Nobel Prize. “We may miss certain topics and candidates because we are biased and have a biased and narrow view of what is an important chemical discovery. We may need to think outside the box.”

She agrees with some people that part of the reason for the scarcity of women’s awards is the systemic disadvantages women face throughout their careers. But she added that this explanation is not the whole story. When talking about the Nobel Committee, she said: “This is a passive way to solve the problem… We also need to solve this problem ourselves.”

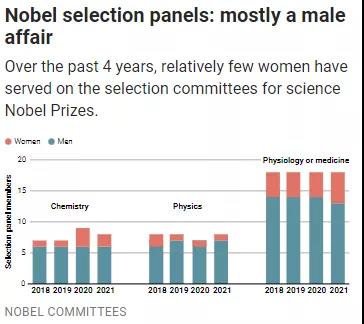

Nobel Prize observers said that there is room for improvement in the composition of the selection committee itself. The members come from academicians of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (Physics and Chemistry Committee) and professors from Karolinska Institute (Physiology or Medicine Committee). This year, the Physics Committee has 7 men and 1 woman, and the Chemistry Committee is composed of 6 men and 2 women. The Physiology or Medical Committee has the highest proportion of women, with 13 men and 5 women.

In the past 4 years, relatively few women have served on the Nobel Prize Selection Committee

Thomas Perlmann, secretary of the Physiology or Medicine Committee and neurologist at the Karolinska Institute, wrote in an email to the journal Science: “We must work to solve the problem of underrepresentation of women in leading academic positions. Thanks to With new recruitments in the past decade or so, the proportion of women [in the committee] is now similar to the proportion of women full professors in [the Institute].”

Wittong Stafshede is satisfied with the number of women in the chemistry committee. “I’m glad we are two.” She said that she found her presence very helpful because the committee has been having more and more discussions on gender equality issues and she was able to share first-hand information. “I have experienced a lot of the unfavorable norms and prejudices we talked about.”

Olsson said the committee did not consider gender issues when discussing the Nobel Prize. “The focus is on science.” But she believes that it is important for women to participate in the selection process and ceremonies because they can be role models. “We make sure that women are present and give awards.”

Wittung-Stafshede said: “The few women we hold in senior positions in academia are used to do committee work in large numbers, usually too much, and often too much. In order to save women’s time, we should treat this with caution. One point. But as far as the Nobel Prize Committee is concerned… this point is very important. It sends a clear signal that we care about this topic.”

Visibility is not the only key. Handelsman believes that a more transparent process may prompt nominees to add more female names to candidates. She said: “For most people, how people get into any possible nomination list is a mystery. If women don’t know what this political process is, then they cannot put themselves in the right environment, nor can they interact with them. Connect with the right people who can help them get nominations.”

Reference materials:

https://www.science.org/content/article/one-reason-men-often-sweep-nobels-few-women-nominees

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.