Smoking aggravates genetic mutations in bronchial basal cells

- Normal Liver Cells Found to Promote Cancer Metastasis to the Liver

- Nearly 80% Complete Remission: Breakthrough in ADC Anti-Tumor Treatment

- Vaccination Against Common Diseases May Prevent Dementia!

- New Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Diagnosis and Staging Criteria

- Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s Disease: New Nasal Spray Halts Cognitive Decline by Targeting Toxic Protein

- Can the Tap Water at the Paris Olympics be Drunk Directly?

- Should China be held legally responsible for the US’s $18 trillion COVID losses?

- CT Radiation Exposure Linked to Blood Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- FDA has mandated a top-level black box warning for all marketed CAR-T therapies

- Can people with high blood pressure eat peanuts?

- What is the difference between dopamine and dobutamine?

- How long can the patient live after heart stent surgery?

Smoking aggravates genetic mutations in bronchial basal cells.

“Nature” sub-issue: 23 packs of cigarettes per year, gene mutation is “big”! Scientists have found that smoking aggravates genetic mutations in bronchial basal cells, peaking at 23 packs of cigarettes per year

Smoking is one of the main “accomplices” of lung cancer, it is already a certainty [1].

Chemicals in cigarettes, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can cause DNA damage in cells and lead to cancer-related genetic mutations [2].

However, a phenomenon that cannot be ignored is that 70% of smoking-related deaths occur in the elderly, and 80-90% of lifetime smokers do not develop lung cancer [3, 4].

This has also become an excuse for many smokers to “swallow and smoke” without fear.

Several studies have shown that there are a large number of somatic mutations in tumor cells of lung cancer patients with a history of smoking [5].

However, there is a lack of research on the somatic mutation of distal bronchial basal cells, the major progenitor cells of squamous cell carcinoma [6].

In addition, few quantitative and systematic studies have explored the effects of age and smoking on genetic mutations.

Based on the above phenomenon and previous research, researchers from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the United States collected distal bronchial basal cells from 14 never-smokers and 19 smokers of different ages, and carried out Single-cell whole-genome sequencing, quantitative analysis of mutations in a single basal cell, found that genetic mutations increase with age, and smoking will greatly aggravate mutations.

Another interesting finding is that the mutation level increases with smoking, but once it exceeds 23 packs per year, the mutation level does not increase significantly.

The research results were recently published in the prestigious journal Nature genetics [7].

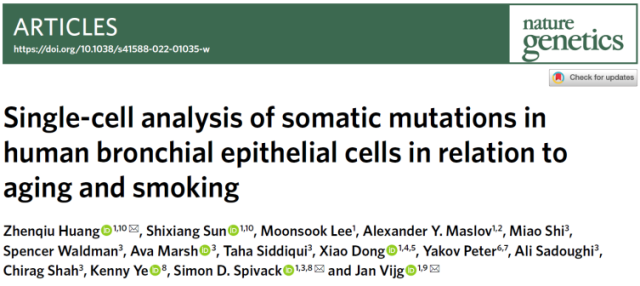

The study first explored the effect of age on genetic mutations.

The researchers quantitatively analyzed the genetic mutations in the basal cells of never-smokers and found that the median values of single nucleotide site variants (SNVs) and insertion deletion mutations (INDEL) in the nucleus increased with age.

There was a high trend where the changes in SNVs were statistically different (Fig. 1).

This suggests that even without smoking, the level of genetic mutations in distal bronchial basal cells increases with age .

Figure 1. SNVs (left panel) and INDELs (right panel) increase with age

Figure 1. SNVs (left panel) and INDELs (right panel) increase with age

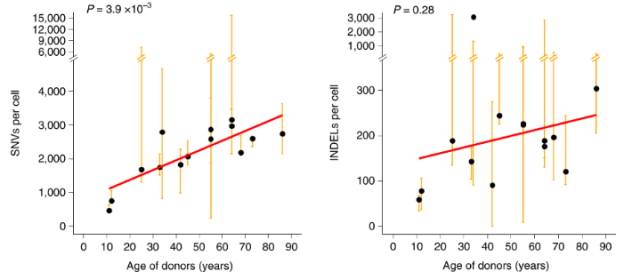

The researchers further analyzed the gene mutations in the basal cells of smokers and found that the median values of SNVs and INDELs in smokers also increased with age, and the increase rate of SNVs was significantly higher than that in non-smokers .

This suggests that smoking exacerbates genetic mutations in bronchial basal cells with age (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Median SNVs (left) and INDELs (right) increased with age in smoking and non-smoking groups

Figure 2. Median SNVs (left) and INDELs (right) increased with age in smoking and non-smoking groups

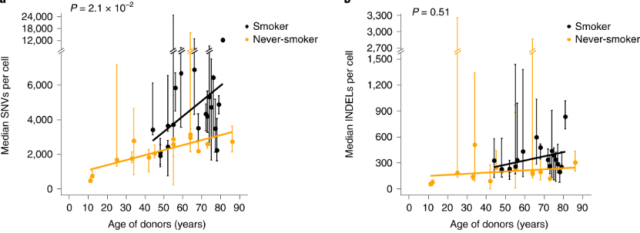

The researchers also analyzed the effect of smoking on genetic mutations.

During the course of the study, a particular participant (1320), an 81-year-old light smoker (6 packs per year) and newly diagnosed with lung cancer, was found to be highly mutated in all 6 nuclei tested.

Mutations in DNA repair genes and multiple tumor-driving genes were found in the nuclei of four of these cells, suggesting that these cells may be derived from the same cell clone with malignant changes.

When this participant was excluded, the gene mutation frequency also increased “straight” with the increase in smoking, however, when the annual smoking exceeded 23 packs (median), the gene mutation frequency increased less “rapidly” (Figure 3) .

This is true, the more cigarettes you smoke, the more “active” your genes are mutated. Of course, when people who can’t quit smoking see this, they must not think “then I’ll be fine if I smoke more”.

Because the accumulated gene mutation is not a simple factor that causes lung cancer, even if “smoking a few more packs of cigarettes” will not make the gene mutation more, it may promote the occurrence of lung cancer through other ways.

Figure 3. Median SNVs increased with age when smoking less than 23 packs per year

Figure 3. Median SNVs increased with age when smoking less than 23 packs per year

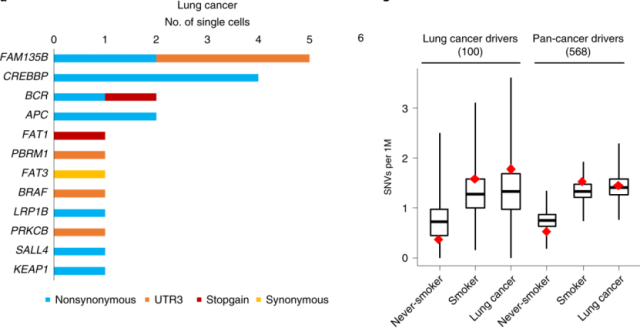

Now that tumor driver genes are important in tumor development, the researchers analyzed the samples for mutations in known lung cancer and pan-cancer driver genes.

It was found that lung cancer driver gene mutations and pan-cancer driver gene mutations were present in 11% and 50% of the nuclei, respectively, but this was not statistically different in the analysis of smoking related lung cancer (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The number of nuclei containing lung cancer driver gene mutations (left); the number of SNVs in lung cancer driver genes and pan-cancer driver genes in non-smoking, smoking, and lung cancer groups

Figure 4. The number of nuclei containing lung cancer driver gene mutations (left); the number of SNVs in lung cancer driver genes and pan-cancer driver genes in non-smoking, smoking, and lung cancer groups

Just like water scars, when cell genes are damaged and repaired by various internal and external stimuli, gene mutations will appear and leave traces, which we call mutation characteristics, which can be used to infer to a certain extent. which variants [8].

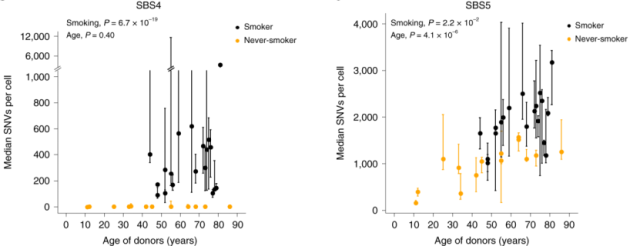

Which mutational signatures were associated with age or smoking were also analyzed in this study.

It was found that SBS4 (single base substitution 4) was only present in the bronchial basal cells of smokers.

SBS4 has been reported to be the main mutational signature of lung cancer with smoking history.

The above suggests that SBS4 is the “wound” left by smoking in the genome. In addition, the study found that SBS5 was not only related to smoking, but also positively related to age (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The relationship between the median value of intranuclear SNVs containing SBS4 (left) and SBS5 (right) and age in smoking and non-smoking groups

Figure 5. The relationship between the median value of intranuclear SNVs containing SBS4 (left) and SBS5 (right) and age in smoking and non-smoking groups

In addition to somatic mutations, germline mutations inherited from parents are also associated with the development of lung cancer.

The researchers also analyzed genetic background-related mutations in distal bronchial basal cells.

One notable result showed that 2 lung cancer participants with a history of smoking developed 2-fold higher levels of SBS4 on the AKR1C2 gene, which encodes a protein that is an important PAH “antidote.”

It is suggested that the mutation of this gene may be an important factor that smoking easily induces lung cancer.

Since Columbus brought tobacco from the American continent more than 500 years ago, to today, every pack of cigarettes is marked “smoking is harmful to health”, tobacco has witnessed the history of human society.

Tobacco has been used to treat diseases at first, and now it has been proven to cause diseases.

It is also accompanied by changes in the types of human diseases, an increase in average life expectancy and the development of medicine.

With the appearance of the first report on bronchial lung cancer caused by smoking in 1950, scientists’ exploration and verification of tobacco-induced cancer has not stopped.

Based on previous research reports, this study confirmed that smoking increases the risk of lung cancer by promoting somatic mutations in normal bronchial basal cells .

More importantly, the study added age as an important factor, demonstrating that genetic mutations in distal bronchial basal cells also increase with age, and smoking increases the frequency of genetic mutations.

In addition, most smokers do not suffer from lung cancer, which is explained in this report. Possibly due to the increase in the accuracy of DNA repair or the reduction of DNA damage, the gene mutations associated with the development of lung cancer are reduced, thus reducing the risk of lung cancer.

As you read this, how many people in the world are lighting that puff of smoke? Who controls tobacco, and who controls tobacco?

References:

1. WD Flanders, CA Lally, BP Zhu, SJ Henley, MJ Thun. Lung cancer mortality in relation to age, duration of smoking, and daily cigarette consumption: results from Cancer Prevention Study II. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19) :6556-62.

2. JE Kucab, X. Zou, S. Morganella, M. Joel, AS Nanda, E. Nagy, et al. A Compendium of Mutational Signatures of Environmental Agents. Cell. 2019;177(4):821-36 e16.

3. DM Burns. Cigarette smoking among the elderly: disease consequences and the benefits of cessation. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(6):357-61.

4. A. Crispo, P. Brennan, KH Jockel, A. Schaffrath-Rosario, HE Wichmann, F. Nyberg, et al. The cumulative risk of lung cancer among current, ex- and never-smokers in European men. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(7):1280-6.

5. LB Alexandrov, YS Ju, K. Haase, P. Van Loo, I. Martincorena, S. Nik-Zainal, et al. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science. 2016;354(6312):618 -twenty two.

6. R. Shaykhiev, R. Wang, RK Zwick, NR Hackett, R. Leung, MA Moore, et al. Airway basal cells of healthy smokers express an embryonic stem cell signature relevant to lung cancer. Stem Cells. 2013;31( 9):1992-2002.

7. Z. Huang, S. Sun, M. Lee, AY Maslov, M. Shi, S. Waldman, et al. Single-cell analysis of somatic mutations in human bronchial epithelial cells in relation to aging and smoking. Nat Genet. 2022;54(4):492-8.

8. LB Alexandrov, S. Nik-Zainal, DC Wedge, SA Aparicio, S. Behjati, AV Biankin, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415-21.

Smoking aggravates genetic mutations in bronchial basal cells

(source:internet, reference only)

Disclaimer of medicaltrend.org

Important Note: The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical advice.